Executive summary

Policymakers everywhere face trade-offs between the economic, political and strategic effects of the economic security decisions they make — like how to affordably diversify sources of energy supply or whether to approve lucrative new foreign investments in critical infrastructure. These economic security issues are not new but the concept of ‘economic security’ itself is still not well-defined.

Defining and achieving economic security is getting tougher as US-China rivalry, climate change, accelerating technology development and China’s significant and evolving role in the global economic landscape sharpen the trade-offs that economic security policymakers face. Deep global economic connections and sophisticated markets mean that economic security issues today can be complex and costly: they involve supply chains, growth and innovation as much as deterrence, commitment and pressure.

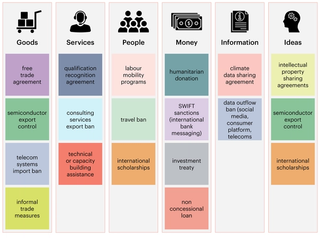

This report identifies the common thread that links together the wide range of economic security issues facing Australian policymakers today — from access to critical minerals to technology competition to global financial sanctions. Fundamentally, economic security is about how the state decides to manage the risks and opportunities of global flows of resources — goods, services, people, money, information and ideas — in an interconnected and dangerous world. This definition encompasses, for example, the complex opportunities and challenges posed by China for Australian economic security policymakers.

Deep global economic connections and sophisticated markets mean that economic security issues today can be complex and costly.

This report analyses economic security policies used by the United States and Japan over the last century to manage the risks and opportunities of global resource flows in an interconnected and dangerous world. The report also considers the current economic security institutional structures employed by those countries and draws a key lesson for Australia — that Canberra could benefit from a ‘joined-up’ economic security policy group, comprised of officials. The group should link government and external nodes involved across the economic security landscape together. Better communication and coordination can help Australia to strengthen its response to economic security challenges and seize opportunities.

An Australian economic security group will need a practical approach to navigate the trade-offs of economic security decisions with rigour and nuance. This report introduces a strategic playbook built to help guide policymakers across government away from dangerous outcomes and unintended consequences — and towards Australia’s desired economic security future. The playbook identifies the policy framework that will shape Australia’s economic security future: the economic carrots (which expand global resource flows) and the sticks (which reduce flows) that have economic, political and strategic effects. The report road tests the playbook using recent US advanced semiconductor policies as a case study, highlighting the potential for new policy insights in a strategically important and complex market environment.

To improve outcomes for Australia, the playbook is designed to embed three state-driven actions: the scanning, sharing and shaping activities needed to tackle economic security issues. The ‘Scan–Share–Shape’ approach for Australian policymakers introduced in this report, and briefly detailed below, could reveal asymmetric economic security advantages for Australia, Japan the United States and others that are persuasive across their regions. These include Australia’s attractive education and labour markets, market access, and exports to drive regional clean energy transitions and food security. In a world where partnerships matter, these and other credible economic carrots offer Australia enduring strategic benefits. They also complement other economic security tools, like those economic sticks that are carefully honed to create a ‘small yard with a high fence’1 of denied economic activity, which can add to pressure and deterrence.

Policy recommendations

In practice, Australian policymakers can use the strategic playbook — based on a rigorous approach informed by new research — outlined in this report to make Australian economic security policies as part of a ‘Scan–Share–Shape’ approach. This will enable policymakers to identify economic security tools and calibrate them to move Australia towards desired economic security outcomes and away from dangerous or unintended outcomes.

Scan

Australia can entrench and expand its economic statecraft capabilities by scanning to identify paths towards desired geopolitical outcomes, like greater prosperity and regional security, and off ramps to undesired or dangerous futures. Scanning should identify current capabilities — like a social safety net, critical minerals and research assets — and identify new ones, like boosting our data and analysis capabilities on global resource flows.

Key recommendation: Stand up a multi-agency group of strategic economic security nodes across government to drive the design of global resource flows analysis capabilities, coordinate scanning for economic security risks and opportunities, and maintain external links to share ideas and expertise. The group should meet regularly to ensure policymakers are equipped to seize economic security opportunities and avoid risks.

Share

Policymakers can share strategic economic security expertise and ideas across existing public and private sector networks to enhance economic statecraft policymaking and to help build a social license for those policies.

Key recommendation: Build and maintain links between public economic security nodes and external nodes including researchers, firms and community groups as well as global leaders in economic statecraft, like Japan.

Shape

Find ways to shape the decisions of individuals, firms and states using economic incentives that advance Australia’s multidimensional global interests (economic statecraft) alongside other tools.

Key recommendation: Shape decisions to achieve policy goals like boosting deterrence or pressure as well as goals like improving cooperation with partners and promoting regional stability. Evaluating the full range of opportunity costs would help identify ways to raise Australian capabilities and identify competitive tools.

Key examples

- Boost resilience and capability-enhancing tools that provide deterrent and buffering effects. For example, broad-based research incentives, which can lead to serious economic and strategic dividends, and education and training policies that build Australian workers’ capacity to adjust to technology and other shocks.

- Sustainably and carefully expand Australia’s attractive economic carrots that offer enduring strategic effects, like access to labour and education markets, which help reduce regional vulnerabilities by boosting long-term capabilities and underpinning strong political relationships. In a similar vein, scope options to send credible signals of Australia’s future capacity and intent to drive regional energy transitions — through clean energy exports and critical minerals partnerships — and food security.

- Take an integrated, rigorous approach to working with the United States, Japan, the European Union (EU) and others on designing economic sticks and carrots that deter and pressure to help manage the multidimensional risks posed by states like China and Russia. For example, Australia can work with the United States, over time, on ways to complement a ‘small yard, high fence’ de-risking approach with enduring US carrots that resonate in the region — like US market access for Southeast Asia and beyond. These will help incentivise coordination to shape decisions in both countries’ interests and to balance the effects of China’s key role in supply chains and US sticks like trade policies that draw states closer to China economically (through lengthening supply chains). Partners like Japan will be important in efforts to work with the United States on trade carrots given complex US domestic constraints.

Introduction: What is economic security?

‘Economic security’ is an old concept, but it is still inconsistently defined. Today, economic security issues centre around states’ use of global economic connections — including bilateral dependencies and vast global markets — in ways that affect other states’ economies and security. For example, Russia’s use of energy supply chains to pressure European countries over their support of Ukraine, US export controls aimed at delaying growth in China’s advanced tech capabilities or China’s denial of rare earth elements to Japan.

Recently, economic security has become a focus for international economic and security policymakers. Global economic connections always present risks and opportunities but recent events like the COVID-19 pandemic, a more dangerous international security environment and advances in technology capabilities have focused the minds of policymakers everywhere on economic security. Today’s economic security issues range across the security of global supply chains, future prosperity, development prospects, the resiliency of critical infrastructure and global standard-setting.

This report explores economic security policies across time and place — and identifies a common thread. Essentially, economic security is about a key question for the state: how does the state decide to manage the risks and opportunities of global flows of resources — goods, services, people, money, information and ideas — in an interconnected and dangerous world?2

This report then considers how Australia can enhance its economic security (or how it can best manage the risks and opportunities of global flows of resources). This report argues that economic security requires calibrating economic levers of statecraft, which ultimately increase or decrease the flows of resources between Australia and other countries, alongside other statecraft tools. Carefully calibrating its policy settings will help Australia navigate key economic security issues like US-China rivalry, cascading global shocks and opportunities to drive new energy and technology systems.

Doing so requires a robust approach — this report introduces a framework — embedded in a practical approach for guiding the evaluation and design of policies that move Australia towards its desired economic security future. Certain economic tools can help Australia shape decisions that advance its economic security and other interests. This requires balancing goals — between a strategic vision, national security and future prosperity — with nuance in an age of deep global economic connections. Too much emphasis on narrowly defined security effects or economic outcomes can reduce both prosperity and national security. For example, policies that incentivise uncompetitive firm behaviours, like rent seeking, can curb innovation and ultimately harm Australia’s strategic and economic outlook. The strategic framework and the practical ‘Scan–Share–Shape’ approach introduced in this report are designed to help balance these goals by integrating the economic, political, psychological, environmental, and other factors at stake in economic security issues.

Australia’s economic security

Australia’s economic security agenda is shaped by the nature of its economy (a net importer of most technologies with concentrated global economic connections in sectors like mineral resources and agriculture) and by its security relationships, notably the US alliance. For example, US-China competition — particularly in critical technologies — is tilting countries towards economic connections based on security relationships and common political systems (rather than comparative advantage), leading to higher prices and potentially disrupted supply.3 As a net technology importer, this sets Australia’s alliance and key partner relationships in tension against its prosperity.4 Australian decisions about emerging economic security issues, like controls on technology trade and investment, will bring this tension clearly into focus.

At the same time, economic links drive prosperity and give Australia regional influence. For example, Australian iron ore exports to China increase Australian wealth and are valued by China, but China is also willing to destroy or reduce some bilateral economic ties to try to achieve its geopolitical goals.5 Another example is the flow of people entering Australia on working visas who boost the Australian economy and build regional influence through deepening Australian connections with their countries of origin.6 This means that Australia’s economic security agenda also includes the global economic links that can help it manage threats by adding to deterrence and underpinning strong political relationships, while also driving the development of new energy and technology systems.

Economic security over time

As far back as ancient Greece, states have looked to international economic exchange to boost national wealth, enhance economic and military capabilities, accelerate innovation and underpin relationships with other states — friendly or hostile. A famous early economic security policy was Athens’ imposition of a trade boycott on the city-state of Megara, which may have triggered the Peloponnesian War.7

Unlike ancient Greece, modern economic security is complex and interconnected, due to advances in technology and deep global markets. Global exchange (or flows of resources) between states has evolved from simple exchanges of goods, people or money to include services, information and ideas, and combinations of these.8 This has occurred as advances in technology fuelled industrial revolutions that allowed states to develop more complicated production processes and innovation pathways that rely on flows of ideas and information between states. This is also due to specialisation and falling costs of transporting resources between states which, have led to deeper and more complex international markets. The development of digital and converging technologies has transformed economic activity and created a ‘digital backbone of society’,9 which has expanded the definition of economic resources to encompass services, information and ideas.

As far back as ancient Greece, states have looked to international economic exchange to boost national wealth, enhance economic and military capabilities, accelerate innovation and underpin relationships with other states — friendly or hostile.

Since the early 20th century, individual states have played varying roles in this transformation of global economic activity, reinforcing or creating an uneven distribution of global resources. For example, since the Second World War, the United States has played large roles in, among others, financial markets, education services, innovation ecosystems and advanced technologies like avionics systems and software tools for semiconductors. More recently, China has come to dominate the production and export of many manufactured goods, built up large excess savings and developed a lead on the United States in some advanced technologies like supercomputing and renewable power equipment. Other states play key roles in markets like capital goods and automobiles (parts of the European Union), energy goods (like Russia and Saudi Arabia), data resources and IT services (India), and raw materials (for example, Australia and Brazil).

Today, a multidimensional struggle between the United States and China is playing out in the economic domain — leading to a focus on economic security by many countries — as well as the military and information domains. Some statecraft tools used by the United States and China are aimed at shaping international economic exchange to take positions in the markets that are likely to positively shape their future economic security — by boosting capabilities, influence and prosperity in the future. The use of military statecraft tools like theft and espionage by China and others has also led to economic and strategic effects that have precipitated the use of economic statecraft tools by the United States, the European Union and others in response.10

An important characteristic of economic security issues is that the economic domain is also the arena in which states face some combination of domestic challenges due to changing labour markets, enormous energy transitions, persistent inflation, debt distress and stagnant growth. These opportunities and challenges in the economic domain lay the scene for the topic of this report: defining economic security and policy options to enhance Australia’s economic security amid complex economic interdependence.

Today, a multidimensional struggle between the United States and China is playing out in the economic domain — leading to a focus on economic security by many countries — as well as the military and information domains.

Policy vignettes

Countries have been using state-led economic policies for national security, economic and other purposes for a long time. Three economic security policy vignettes are introduced here to underline the issue at the heart of economic security — how countries decide to manage the global exchange of economic resources. These vignettes describe past economic security issues and the various approaches used by two of Australia’s key partners, the United States and Japan, to boost economic security. The three typologies remain relevant today because the forces involved, including economic forces (like markets and trade policies) and the political and psychological forces (like domestic concerns and signalling intent and credibility) are at work today.

1. The Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls (CoCom), 1948–1994

Secretly formed in late 1948 by the United States and the other members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO),11 except Iceland and including Japan, the Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls (CoCom) restricted the flow of economic resources (technology goods and other resources) to the Soviet Union and the communist bloc states until 1994. The group maintained an embargo list of items, agreed by consensus, that could not be sold to the bloc. Each member country used its own set of policies to restrict resource flows to the bloc — for example, the United States used the US Arms Export Control Act. Over time, CoCom expanded to include Australia.12 Disbanding in 1994, the group was replaced by a multilateral regime, the Wassenaar Arrangement, of which the United States, Australia and Japan are three of the 42 members. The Wassenaar Arrangement continues to promote transparency and responsibility in the transfer of sensitive technologies and conventional arms with the support of its members today.

The goals of CoCom varied among its members and over time. A clear goal of the group was to reduce the military capabilities of the Soviet Union. The group disagreed on other goals, reflecting different views of the nature of the problem. The United States was primarily worried about expanding Soviet territory and its influence around the world, including a communist model of development gaining broad traction in other countries, and wanted to demonstrate US resolve to resist communism.13 The United States was specifically concerned about Soviet trade expanding — and therefore Soviet influence — with Japan and India.14 Concern about the Soviet threat varied over time among European members, that were dependent on the United States for defence against the Soviet Union and for post-war economic recovery.15

CoCom successfully imposed costs on the Soviet Union that likely forced a reallocation of Soviet resources to sustain its military spending.16 It is harder to measure how (or if) CoCom contributed to US goals of minimising Soviet expansionism and influence globally given the multiple factors at play. There is more evidence that the United States was able to meet its goal of demonstrating resolve to resist communism: by disrupting ‘business as usual’ the embargo reinforced the US view — to allies, partners and the rest of the world — that communism was a threat.17 Working against the group’s goals however, CoCom also imposed economic costs on its members, strengthened Soviet control of bloc countries and increased Soviet self-sufficiency.18

Maintaining cooperation among the group members was challenging — US leadership and dominance of resources were needed to sustain unity. When members of the group perceived a low threat from the Soviet Union, incentives to reduce their export controls and take market share were powerful, especially when the United States was not dominating technology export markets. For example, cooperation among CoCom members was high in the 1960s, when the US government controlled the production of most of the goods considered ‘strategic’ by CoCom members and members perceived a high threat from the Soviet Union, evidenced by the Cuban missile crisis and placement of US missiles in Europe. In the 1970s and 1980s, cooperation was harder as other CoCom members built economic stakes in the production of ‘strategic’ goods and as members’ perceptions of the Soviet threat receded.

Research suggests that as members became more powerful economic players, the ability of the United States to lead — to commit to leadership responsibilities and respect its privileged position — helped to unify the group. US leadership was important because of the informal nature of the group, which made it hard to enforce rules and relied more on the ability of the United States to engender cooperation by demonstrating credibility and respect.19 This made shrewd US military assessments important for maintaining credibility and relied on perceptions of the membership that the United States was not ‘overreaching’.20

2. US freer trade policies, 1944–1962

From 1944 to 1962, the potent economic statecraft tool used by the United States to strengthen alliances and international stability was free trade policy, contributing directly to a global balance of power that was more favourable to the United States, underpinned by multilateral export controls and military and information tools. At the time, foreign aid received more public attention, but the substantive economic action was taking place in the trade arena: “the American use of trade policy to construct an international economic order based on non-discriminatory trade liberalization in the period after World War II was one of the most successful influence attempts using economic policy instruments ever undertaken,”21 argues the author of the pre-eminent book on economic statecraft, David Baldwin (1985).

The US turn to free trade began in 1934 with the US Reciprocal Trade Act,22 but it was the introduction of the Bretton Woods agreement in 194423 which laid the cooperative foundations for the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 194724 that solidified the US approach: multilateral freer trade policies that helped the United States shape the post-Second World War international environment. These objectives were large and multidimensional. Breaking US objectives down into discrete goals, Baldwin suggests that the United States was attempting to strengthen military alliances, promote economic recovery from the war — including boosting US allies that helped to contain the Soviet Union — in Western Europe and Japan, ensure access to strategic raw materials, stimulate economic development in poor countries, create markets for American exports, and create an international atmosphere conducive to peace and security.25

In turning to a freer trade policy, the United States used a powerful statecraft tool that relied on a meaningful commitment: it offered other countries the ‘carrot’ (or promise) of reducing US trade barriers on a reciprocal basis. For example, the United States was a key participant in the creation of the GATT, the precursor to the World Trade Organization (WTO). To meet its GATT obligations, the United States introduced policies to promote freer trade such as the Trade Agreements Extension Act of 1951 and the Trade Expansion Act of 1962.26 The United States also used complementary tools of military and diplomatic statecraft that helped stabilise the international political environment and promoted a vision of a liberal economic order.

In concert with other statecraft tools, US trade policy directly and indirectly contributed to its national objectives. Most obviously, freer trade was good for economic recovery in Europe and Japan, securing access to raw materials, stimulating wider economic development, and creating markets for US exports. More subtly, the policies also helped the United States tighten its bonds with increasingly economically powerful alliance partners and contributed to creating a relatively stable international environment over the period.27 Freer trade was pivotal to US diplomat George Kennan’s containment strategy of countering the spread of Soviet influence using economic assistance to allies, and psychological warfare against the Soviet bloc to stop Soviet economic and political expansion.28

3. The transformation of Japan’s post-war economic strategy, 1945–present

Since 1945, Japan’s economic strategy has transformed significantly. In the wake of Japan’s catastrophic defeat in the Second World War, Tokyo used export promotion, multilateral trade and foreign aid to help achieve its international economic and security goals of boosting growth and reintegrating into the global system. A pivotal shift occurred in the early 21st century under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Japan opened its markets to foreign investment, championed trade liberalisation, and led efforts to build regional economic and security institutions to uphold a rules-based order. Abe’s policies aimed to enhance Japan’s economic security in the face of its primary strategic threat: China. Recently, Tokyo has increased state involvement in managing economic connections, particularly with China. In 2021, an economic security minister was appointed and an economic security team was established in Japan’s National Security Council. This has seen Japan introduce new policies like minilateral export and investment controls on advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment.29

After the Second World War and its exit from the League of Nations, Japan’s early post-war economic strategy focused on signalling its return to international institutions and revitalising its economy.30 With US support, Japan joined the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank in 1952 and the GATT in 1955. Membership of these bodies facilitated Japan’s reintegration into the international system and contributed to its prosperity, complemented by export promotion policies and US reliance on Japan as a manufacturing base for defence equipment during the Korean War.31 Japan also used foreign aid (Official Development Assistance or ODA) under its ODA Charter to make wartime reparation payments and to rebuild and maintain strong post-war relationships across the Indo-Pacific.32

During the 1980s and 1990s, Tokyo looked to economic tools to manage trade frictions with the United States. There were rising concerns in the United States about dependence on Japan in sensitive sectors, like semiconductors, and perceived protectionist policies that disadvantaged US firms. Tensions escalated when revelations surfaced about Japanese firm Toshiba and a Norwegian firm violating CoCom export controls by supplying sensitive technology to the Soviet Union.33 To help manage US pressure, Japan embraced the new World Trade Organization (formed in 1995) and, in 1989, collaborated with Australia to establish the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum to keep the United States engaged in the region.34 As Japan’s economy expanded, it kept up its ODA spending, increasingly directing it towards Southeast Asia and India. Towards the end of this period, concerns grew about China’s rise due to its rapid economic growth and assertive security and trade policies.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, in particular, set Japan on a new economic trajectory to help Japan compete with China’s economic policies and its strategic ‘tenacity’ while recognising the importance of the relationship.

In the first two decades of the 21st century, Tokyo shifted its economic strategy to address its strategic rival, China. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, in particular, set Japan on a new economic trajectory to help Japan compete with China’s economic policies and its strategic ‘tenacity’ while recognising the importance of the relationship.35 Japan promoted foreign investment and implemented trade liberalisation measures to bolster its economy, making it more resilient and efficient. Abe also aimed to strengthen regional economic institutions supporting a rules-based order, which underpinned his ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ concept introduced in 2016.36

On the trade front, Japan pursued liberalisation to compete with China and reinforce the regional economic order.37 Tokyo signed large regional trade agreements like the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP, excluding China) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP, including China) to shape the contours of regional economic exchange and as ways to engage and counter China.38 Japan secured other key trade deals during this period, including with the European Union and the United States.39 Abe also tried to integrate the United States and India into the regional economic order, although both countries withdrew from major agreements (the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2017; India from the RCEP in 2019). Abe’s trade liberalisation substantially increased the proportion of Japan’s trade covered by Free Trade Agreements and economic partnerships, rising from 17 per cent to over 80 per cent.40

As part of its economic strategy shift, Japan adjusted its aid and regional investment approach. It ceased aid to China and focused on India, which became the largest recipient of Japanese ODA in 2003.41 Under Abe, Japan increased the use of aid to boost non-military regional capabilities and assist states facing pressure from China in the South China Sea. In recent years, Japan has prioritised resources for regional infrastructure investments, working with the United States, the European Union, Australia and others. These efforts aim to provide high-quality infrastructure supporting growth, future investment, and export markets, and to respond to China’s increasing infrastructure investments in the region.42

At the bilateral level, Japan has adopted a state-led approach to handling its economic ties with China. Triggered by China’s Belt and Road Initiative launch and domestic technology goals, the 2010 rare-earths export incident43 and concerns about US economic engagement in the region,44 Tokyo has implemented policies like investments in local capabilities and advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment export and investment controls under the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Law (see Box 1 on economic statecraft involving semiconductor supply chains). These policies aim to reduce Japan’s economic vulnerabilities while continuing to benefit from China’s growth.

Japan’s economic strategy has changed considerably since 1945 — the aims and tools of Japanese economic strategy have transformed. Today, Japanese economic strategy aims to acknowledge the economic security equities of China’s rise for Japan: the regional prosperity benefits and the strategic risks. Signalling the high priority Japan places on economic security issues, Japan was the first country to appoint a Minister for Economic Security (in 2021) to try to integrate the broad set of policy issues that encompass economic security across the Japanese government.45

Policy lessons

These three policy vignettes illustrate the core issue at the heart of economic security policymaking: the state makes decisions about how to manage flows of resources amid risks and opportunities to national prosperity and security. The type of resources involved in economic security policies vary and can involve policies to expand (carrots) or restrict (sticks) global resource flows. These features and lessons from the vignettes for economic security policymaking are summarised in Table 1.

The type of resources involved in economic security policies vary and can involve policies to expand (carrots) or restrict (sticks) global resource flows.

Importantly for Australian and other policymakers, the examples also show that geopolitical circumstances can change the weighting that policymakers place on the security, sovereignty and prosperity trade-offs of economic security policies. For example, in the first vignette, CoCom members faced a militarily powerful but economically distant Soviet Union. These geopolitical conditions softened the trade-off between the perceived security benefits (high) and sovereignty and prosperity costs (low to medium) of coordinated technology export controls as described above. In contrast, the third vignette describes Japan’s response to a militarily powerful and economically close China in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Current geopolitical conditions are sharpening countries’ perceived security, sovereignty and prosperity trade-offs of today’s economic security policies. For example, coordinated high-technology export controls that involve high perceived prosperity costs as well as high-security benefits (but which will vary by country, as described in the next section). In summary, a key difference between economic security issues today and those presented in the first and second vignettes is the deep and complex array of resource interdependencies that now weave countries together — which makes understanding global markets and supply chains a key element of economic security policymaking. The framework introduced in this report accounts for this and other economic, political and strategic factors.

As well as changing geopolitical circumstances, countries’ domestic political environments are key variables in formulating economic security policies, making past lessons useful but not wholly prescriptive for today’s policymakers. For example, US domestic support for freer trade is often considered to be lower today than in the 1940s and 1950s.46 US freer trade policies in the second vignette were helped by domestic support from US farmers, firms and workers. Today, potential US economic security policies involving freer trade — like US membership of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) — do not receive the same levels of domestic support.

Lessons from the past are therefore not an argument for exact replication — but past economic security policies and responses illustrate the range of economic, political and psychological forces that are still involved in economic security issues. For example, the mental and emotional effects on leaders and foreign nationals of the United States demonstrating resolve to resist communism through CoCom controls have parallels today in the efforts of the United States, the European Union, Japan, Singapore, Australia and others to condemn and weaken Russia and to signal resolve and intent to China. Past experience is also a reminder of the bigger economic security picture: that economic tools — in concert with military, diplomatic and other tools — can be used to help move states towards geopolitical outcomes in their long-term interests. This is strategic economic security as defined in the next section of this report.

Table 1. Lessons from Economic Security policy vignettes

| Economic security policy vignette | Policy goals | Type of economic security policy | Policy effects | Policy lessons |

The Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls (CoCom), 1948-199 |

|

Economic Sticks: multilateral export controls to reduce resource flows. For example, the US Arms Export Control Act. Targeting resource flows of military equipment, including technology goods and other resources, to the Soviet Union. |

|

Some policy effects worked as intended to reduce the Soviet Union’s military capabilities — while other effects were counterproductive (like strengthening Soviet control of bloc countries). Maintaining group unity was hardest when the United States did not dominate resource markets and the perceived Soviet threat was low. Successful US leadership required demonstrating credibility and restraint, including through shrewd intelligence sharing. |

US freer trade policies, 1944–1962 |

|

Economic Carrots: reciprocal trade barrier reduction to increase resource flows. For example, accession to the GATT. Targeting a wide range of goods, services and investment resource flows. |

|

Most policy effects worked as intended and were self-reinforcing. The policy effects also helped balance some of the tensions created by competing incentives in CoCom. |

The transformation of Japan’s post-war economic strategy, 1945-present |

|

Economic Carrots: multilateral and other free trade agreements, trade liberalisation and foreign aid. For example, promoting the CPTPP and RCEP agreements and Japan’s Official Development Assistance Program under Japan’s ODA Charter. Economic Sticks: minilateral investment and export controls. For example, advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment export and investment controls under Japan’s Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Law. |

|

Trade liberalisation and regional integration efforts have transformed Japan’s economic strategy to meet its major 21st-century opportunities and challenges. Japan’s integrated economic security approach across government has helped it reduce its economic vulnerabilities while continuing to benefit from China’s economy. By appointing an Economic Security Minister and standing up a team in the National Security Council, Japan has been able to adjust economic security policies with more flexibility and integrated design. |

The G7 approach

Against the above backdrop, it is easier to comprehend the reasons for the Group of 7 (G7) leaders introducing the term ‘Economic Resilience and Economic Security’ in Hiroshima, Japan in May 2023. The G7 described this term as rooted in ‘maintaining and improving a well-functioning international rules-based system’47 as a way of defining economic security issues that cover key aspects of international economic exchange of resources. These key aspects include:

- reliability of resource exchange (resilient supply chains)

- the rules of resource exchange (non-market policies and practices, addressing economic coercion, international standard-setting) and

- the physical links through which resource exchange takes place (resilient critical infrastructure, harmful practices in the digital sphere, leakage of critical and emerging technologies).

The focus on economic resilience by the G7 is useful for balancing tensions in the choices countries make about how to manage the international exchange of resources. For example, economic security goals like responding to climate change require networks of resources that are located around the world. Depending on the market, complex webs of resource dependence mean that countries may only reach their goals if other countries do too. In some advanced renewable energy markets like solar energy technology that rely on deep resource networks spread around the world — US economic sticks will slow China down, along with the United States and others (see Box 1: a case study on US statecraft involving semiconductor supply chains).

Strategic economic security playbook

Introducing a strategic economic security playbook for Australia

Weaving lessons from the past into a playbook built to describe modern realities consistent with the G7 approach, this section introduces a playbook that points Australian policymakers towards policies that stack the odds in favour of their economic security and other interests.48 The playbook incorporates a modern update to states’ economic statecraft frameworks alongside an economic, political and psychological understanding of how economic tools work. The playbook helps policymakers focus on key questions, break down policy issues into goals and effects, and consider policy responses that stack the odds in favour of desired outcomes.

Policy principles

Three principles of strategic economic security to underpin policymaking are:

- Keep a steadfast strategic focus by balancing short and long-term priorities: respond to short-term economic security issues as needed but also spend effort on proactively scanning for opportunities and risks involving resource flows that shape the international environment, including overall economic capabilities.

- View economic statecraft as a lever that complements military, information and diplomatic tools. Shaping the international environment is often difficult and costly — relying on only one type of policy tool is unwise. Economic tools can offer benefits like demonstrating credibility without the use of force or generating positive-sum outcomes that continually reinforce relationships. Complementing ‘all arms of statecraft’ approaches49 on the economic front requires joined-up discussions and analysis across government (state and federal), communities, academia and business.

- Use rigorous frameworks, like the playbook proposed in this report, and a whole-of-government approach that prioritises outreach to business, education, community and other sectors, to evaluate the tools and effects of economic statecraft. The economic, strategic, ethical, psychological, political, environmental and other dimensions of different tools of economic statecraft will have varying probabilities of producing desired geopolitical effects. And different parts of government will have varying views on the desired effects of economic security policymaking — balancing policy trade-offs requires a joined-up approach. For example, sanctions or big-ticket infrastructure projects may help to achieve some short-term goals, while laying the groundwork for enduring, deep ties through labour or renewable power market integration can have potent long-term effects and self-reinforcing dynamics.

These principles underpin the playbook proposed here. Considering which strategic economic security policies might work best for Australia requires firstly understanding how economic security tools do — and do not — work.

Frameworks

A nation’s economic security framework — the range of policies that a state can use to manage global resource flows — has evolved with the growing economic connections between states and the increasing complexity of supply chains and innovation ecosystems. There are more tools available and evaluation is more complex. Economic tools can, and have, been used by states to generate effects like using export bans or freer trade policies to alter economic and military capabilities and to underpin stability in the international system.

Not all global resource exchanges are used by policymakers to advance their economic security interests — but recognising the potential economic and security effects of global economic connections is needed to guide strategic policy.

Figure 1. The modern economic statecraft framework — some policy examples

Wielding economic tools

States can use economic tools to shape the decisions of individuals, firms and other states in ways that help advance their economic security and other geopolitical interests.50 The effects of these economic tools can include altering pressure on policymakers, signalling intent or credibility, encouraging a reallocation of resources, expanding foreign export or investment markets, encouraging the exchange of ideas or information resources, and altering policymakers’ intentions. These effects occur through pathways involving economic and non-economic forces (Appendix).

Understanding economic forces like market characteristics and using tools alone or with other states helps determine who is affected by economic statecraft and how, which will have — sometimes large — impacts on the success of economic security policies. For example, a key market characteristic of the global market for luxury yachts is that the consumer base for the product is narrow. This means that an economic sanction on a foreign luxury yacht management company is likely to directly affect a small group of people (which may be a desirable market feature from the perspective of the state imposing the sanction if it wants to target a select group). Economic forces are described in the Appendix.

States can use economic tools to shape the decisions of individuals, firms and other states in ways that help advance their economic security and other geopolitical interests.

The role of non-economic forces — psychological and political — in economic statecraft can help explain why countries use economic tools even if using the tool is costly or if the direct economic effects of the tool are low. Using the same luxury yacht sanction example, levels of economic inequality and the political structure in the targeted country will help determine whether the people affected by the sanction include elite members of society in influential positions. In those cases, the tool may harness psychological forces by raising awareness of the wealth of luxury yacht owners. Firms can also be affected by psychological forces. For example, when the United States, the EU, Japan, Singapore and other countries imposed wide-ranging joint sanctions on Russia in early 2022, firms curbed their activities involving flows of resources to and from Russia.51 This was partly because they were directly affected by sanctions but also because they expected future sanctions and interruptions to business or worried about a backlash if they did not act.52 Combining these effects, the sanction might have small direct economic effects on the targeted country but could add to political pressure on policymakers. Non-economic forces are described in the Appendix.

As this example of a single type of sanction illustrates, sharing insights and expertise in the areas of economics, politics and psychology — among others — are vital for making strategic economic security policy. The policy section steps this out in detail and describes how Australia could do this.

Playbook for Australian policymakers

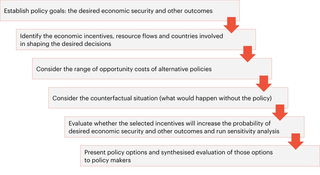

Bringing the modern range of economic tools that shape decisions together with insights into how those tools work, this playbook evaluates how economic carrots and sticks shape decisions to move policymakers closer to their goals. The playbook steps policymakers and scholars through the process of evaluating and designing strategic economic security policies based on the economic, political and psychological forces at work in shaping decisions that advance economic security and other goals.

The playbook is consistent with past and recent definitions of economic security, like the recent G7 definition, and is aligned with social science methods that seek to reduce bias, break difficult problems down into discrete pieces and identify the relevant indicators or measures to focus on. The full version is available at the link below and is summarised in the following figure.

Figure 2. Process for evaluating economic security policies

Playbook application: US semiconductor sticks and carrots

This report now puts the playbook into practice using a topical example: US economic security policies involving semiconductor supply chains.

Leading-edge (the most advanced) semiconductors play a pivotal role in US-China competition because they are deemed indispensable for progressing important areas of innovation like artificial intelligence (AI) and supercomputing. Despite large subsidies for semiconductor manufacturing at home, China currently lags behind the leading-edge semiconductor manufacturers, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), Samsung Electronics and Intel.53 However, Beijing plans to reduce its reliance on foreign firms and dominate semiconductor markets over time.54

In response, the United States unveiled new economic security policies in 2022 (described in detail below). Using both carrots and sticks, the United States aims to maintain ‘as large of a lead as possible’ over China in the production of leading-edge semiconductors.55 US allies with key roles in leading-edge semiconductor production — Japan, South Korea and the Netherlands — later introduced complementary policies (described below).

Policy goals

Primary goal:56

- Alter the AI, supercomputing and other advanced technology capabilities of the United States, China and US allies and partners.

- Slow China’s growth in AI, supercomputing and other advanced technology capabilities and preserve those capabilities for the United States and its allies and partners.

Other goals:

- Reduce US dependence on key leading-edge semiconductor chokepoints (Taiwan).

- Impose costs on China.

- Signal intent, credibility and strength to China, US allies and partners, and other countries.

- As part of a large set of initiatives: avoid kinetic war by altering capabilities, imposing costs and signalling intent and credibility (deterrence).

- Achieve US domestic objectives (important policy goals but not evaluated here as the focus of this analysis is achieving geopolitical objectives).

Economic tools

Sticks: US export controls on semiconductors, advanced supercomputing and semiconductor manufacturing equipment; US Disruptive Technology Strike Force enforcement; US CHIPS and Science Act 2022 funding conditions; US outbound investment rules; and complementary policies of US allies.

Note: the sticks involve markets with high concentrations of production capabilities in the United States, Taiwan, South Korea, Japan and the Netherlands.57

Carrots: US CHIPS and Science Act 2022 incentives for manufacturing, R&D, workforce development and partnerships; investments and partnerships with firms based in US ally states (TSMC and Samsung).58

Resource flows involved: all types of resource flows — goods, services, people, money, information and ideas — are involved. Some resources are more concentrated in the United States or allied and partner countries: leading-edge semiconductor machinery, IP, skills and production. Other resources are more widespread: mature semiconductor skills and production (China, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea and others) and some skilled labour and transferable production expertise and manufacturing (for example, China for advanced packaging production skills and capabilities).

Range of economic and non-economic effects

- Imposes costs on Chinese individuals and firms and the state.59

- Imposes costs on other states via individuals and groups.60 For example, consumers in countries that are net leading-edge semiconductor importers are likely to face higher future costs of compliance with US economic sticks. Another example is that a glut of mature semiconductors is costly for competing firms like Taiwan’s United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC). Overall, a redistribution of resources like investment, intellectual property and high-skilled workers towards the United States will divert some of these resources from other countries that would otherwise have attracted those resources.

- Encourages a reallocation of resources in China towards: semiconductors that are not covered by the rules (mature chips), indigenous leading-edge semiconductor development and other means of obtaining leading-edge semiconductors including sourcing from third countries and theft or espionage.61 This reduces US leverage over China in the future (and vice versa) and is likely to accelerate China’s efforts to reduce its reliance on the United States.

- May deepen economic links between China and other states. For example, exports from China to states in Southeast Asia have risen in response to other US economic statecraft tools like tariffs, which have reshaped supply chains to comply with US policies.62

- Signals US resolve to compete with China and alter its capabilities, which will sometimes include asking allies and partners for support. Also signals to other countries that the United States may not offer some types of economic carrots, like trade and investment deals, and that it plans to use subsidies (sometimes preferencing its allies and partners) to build US capabilities.

- May increase anti-US sentiment among citizens in China, which was already growing.63

- May improve the capabilities of the United States and its allies and partners over the long term if the United States can maintain multiple leading-edge production ecosystems in a high-wage system with strong protections for workers and gaps in specific types of skills and knowledge.64 Success is likely to depend on migration settings, the strength of institutions and time restrictions on subsidies.65

- Add pressure on policymakers in China. Amid an economic slowdown and a relatively brittle political system, such combined pressures could possibly deter costly actions like using military force against Taiwan or possibly accelerate them.66

Opportunity costs

Growth and capabilities: industrial policies, like the production incentives in the US CHIPS and Science Act, are more targeted but also costlier than other methods to promote innovation like broad investments in academic and other forms of research, training programs and infrastructure, and skilled temporary worker and migration programs. These alternative policies are less targeted but can promote a range of forms of innovation and industry without the risks of industrial policies like misuse of funds or reduced dynamism from drawing resources towards state-led initiatives. For example, TSMC estimates that fabrication plant construction costs in the United States are about four to five times more expensive than in Taiwan.67

Consumers: higher-cost substitutes manufactured in the United States may lead to higher costs for consumers there and elsewhere.

Producers: varied effects on producers depending on where they are located and whether semiconductors are inputs (translating to broadly higher costs) or outputs (translating to broadly higher revenues) of firms’ production.

Counterfactual

Without these US economic statecraft policies, China would still have continued to try to develop leading-edge semiconductor production capabilities, using a range of methods like subsidies, technology transfer and intelligence methods to do so. At least in the short term, China would still have been reliant on external supply chain chokepoints to develop this capability. If China had developed these capabilities over time, it might have secured more geopolitical influence and faced fewer constraints to using military tools of statecraft against Taiwan.

If the United States had not deployed these statecraft tools, it is unlikely that rapid development of capabilities in leading-edge semiconductor production would have occurred in the United States in the short term (though the United States had capabilities in other parts of the supply chain).68 This also means that in the short term, it is likely that the United States would have been reliant on key global chokepoints, like Taiwan, for leading-edge semiconductors.

Without the policies, other states — and their local firms — would have had fewer incentives to rapidly deploy strategies to diversify leading-edge semiconductor supply chains (including investment) beyond China (were it to develop production capacity). Outside the United States, some firms would have profited more but may have faced more strategic uncertainty — this is probably clearest for Taiwan but the net effects are less clear for other countries.69

Without these tools and a trend towards using policies that can dampen market dynamism, the United States may have more clearly remained cemented in its pole position as the global leading technology adopter, which is a source of resilience as it is tricky to predict which new technologies will become important and when.70

Evaluation and sensitivity analysis

These US economic tools are more likely to advance some policy objectives than others — how ‘successful’ the United States will be depends on what Washington wants to achieve most. Imposing costs on China and signalling US intent and credibility are likely: there’s already evidence of this.71 Competing incentives in the widespread networks of knowledge and inputs that are needed to create and maintain advanced technology clusters make it harder for the United States to remove links with China while also increasing its lead.72

These US economic tools are more likely to advance some policy objectives than others — how ‘successful’ the United States will be depends on what Washington wants to achieve most.

The profoundly important goal of avoiding war is more clearly addressed in other US statecraft policies, but as part of a broader set of initiatives, these tools will add pressure on policymakers in China. An ongoing challenge for the United States will be managing these competing incentives with allies and partners through credible leadership. As discussed in the next section on policy, a costly and highly credible signal of US leadership would be its commitment to economic carrots that shape the regions where China has deep economic influence.

Using a strategic economic security lens here helped to identify the multiple layers of US — and other countries’ — goals and brought nuance to evaluating each goal according to economic and political realities. Beyond this brief application for illustrative purposes, detailed quantitative or qualitative sensitivity analysis should be conducted for policymaking. For example, changing technology trends, different trade policy settings or geopolitical events could alter the analysis.

Policy options

This report has defined economic security and introduced a strategic playbook to help policymakers evaluate and design economic security policy — but practically embedding this approach involves a wide range of state and non-state actors.

To help policymakers embed a strategic approach to economic security that involves a wide range of stakeholders, this report introduces a ‘Scan–Share–Shape’ model. This policy model is designed to set up processes that will identify economic statecraft tools and calibrate them to move Australia towards desired economic security outcomes and away from unintended consequences. The three buckets of activities — Scanning, Sharing and Shaping — involve many parts of government and rely on external stakeholders in business, research and other parts of society. To consider the institutional settings needed to support these wide-ranging activities, it will be useful for Australian policymakers to consider some global benchmarks. The next section describes the arrangements used by some other countries that are updating or expanding their public sector architecture to manage economic security issues.

This policy model is designed to set up processes that will identify economic statecraft tools and calibrate them to move Australia towards desired economic security outcomes and away from unintended consequences.

Global benchmarks: Who makes economic security policy?

Taking a strategic approach to economic security involves a wide range of state and non-state actors: from individuals and businesses affected by changing geopolitical and economic conditions to high-level policymakers facing uncertainty over global supply chains. The playbook developed in this report is designed to help policymakers evaluate the economic and other levers available, to help manage these wide-ranging economic security issues. Doing so requires some government resources and public sector architecture to carry out economic security policy planning, evaluation and design.

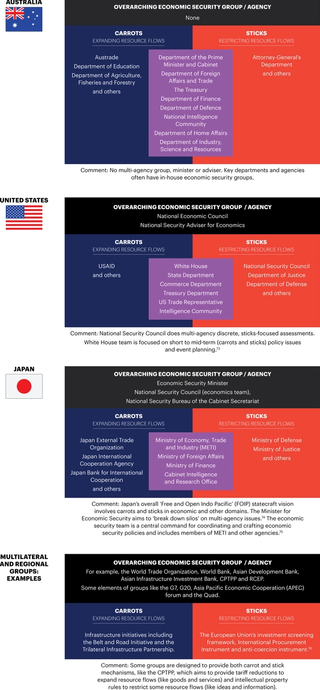

Figure 3 outlines how Australia, Japan and the United States, as well as some international groups, have organised their economic security architecture — the agencies and groups involved with expanding international resource flows and those involved with reducing resource flows. The United States and Japan have designed teams with an overarching view of economic security issues to provide policymakers with joined-up views of the role of global economic exchange to help advance economic, political and security priorities. This will often give economic security policymakers in the United States and Japan a decision-making advantage over other countries by enabling rapid responses to issues like economic coercion or encouraging early identification of new opportunities.

Figure 3. Global economic security policymaking structures

An indicative list of the economic security architecture in select countries and groups — the agencies and groups involved in expanding international resource flows (carrots), reducing resource flows (sticks), or both.

Australia does not currently have an overarching economic security group or agency, but it has economic security groups within key agencies like the Treasury, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (PMC). To implement the ‘Scan–Share–Shape’ approach to economic security that is argued for next in this report, the Australian Government could consider a flexible architecture — like an economic security group made up of multi-agency connection points, as described in the next section.

A Scan–Share–Shape approach

This report introduces a ‘Scan–Share–Shape’ approach that can help to practically embed the strategic economic security playbook in policymaking. In practice, a joined-up effort on strategic economic security policymaking involves three broad groups of activities: scanning, sharing and shaping. These activities will help policymakers identify the range of enduring, complementary and cost-effective forms of economic statecraft that could be deployed to move Australia towards its desired economic security future.

Scan

Scanning activities across government can identify paths towards desired economic security outcomes and off-ramps to undesired futures.

With a range of economic security goals and potential scenarios to consider, scanning should take place in different places with different groups. Multi-agency connection points are needed to combine and synthesise views. For example, more regular meetings of multi-agency groups made up of nodes from key public institutions (see the Australia row in Table 3) could consider the use of economic tools that would benefit Australia, like a sustainable expansion of targeted South Pacific worker and migration schemes, as well as potential threats like effects on the Australian Stock Exchange of the use of US financial sanctions in a Taiwan contingency.

Compared to some other tools of statecraft, economic security scanning does not need to be hugely resource intensive but does require resolve.

One way to organise economic security scanning activities is to join up the activities of existing key nodes at the heart of policymaking identified in Table 3 (like PMC, Treasury, DFAT and DISR) with long-range planning and analysis arms of the state (like ONI and parts of Defence) and new economic security nodes (like Attorney-General’s, Finance, Austrade and other parts of the Intelligence Community) to regularly scan the environment for economic risks and opportunities using an integrated framework. This could result in key reports and ongoing scenario planning that are fed into existing channels for timely analysis and policymaking across government. Importantly, this should bring together expertise in policymaking involving both carrots and sticks and a diverse range of skills in economics, politics and other relevant fields like law, data science and psychology.

A set of tools and conditions to promote economic security scanning are suggested by the playbook presented in this report: access to diverse sets of data and insights, use of futures analysis and a clear aim of integrating views across government to develop strategic economic security policy. Compared to some other tools of statecraft, economic security scanning does not need to be hugely resource intensive but does require resolve.

Scanning recommendations:

- Empower a multi-agency group to think creatively and broadly about credible carrots and sticks that move Australia towards a long-term view of contributing to regional stability and prosperity. Standing up a group with regular nodes in the core strategic economic security departments and agencies could be supplemented with rotating government secondees with specific capabilities beyond economic expertise in areas like data analysis, psychology, regional knowledge and business.

- Develop a best-practice tracking and analysis capability to help predict global resource flows and understand key market and other characteristics — like early indicators of economic preparations for high-risk military activities, and the elasticity of supply and global concentration of resources like rare earths and critical minerals — that will help Australia navigate opportunities and risks while staying open.77 This capability will support existing activities like supply chain data sharing among WTO members and working with regional partners on economic security.78 Ideally, this capability would improve the quality of international economic data available to Australian policymakers and ensure timely data accessibility. This capability would require an investment of resources but would be useful for both policy and intelligence-focused arms of government, including open-source intelligence.79

- As part of this capability, invest in ‘exquisite’ commercial data and intelligence that describe and forecast flows of resources and their second and third-order geopolitical implications. This can help to fill information gaps in understanding international economic resource flows. For example, commercial data and analysis can help policymakers calibrate the design of economic sticks to promote desired outcomes and minimise unintended consequences as well as drive a deeper understanding of states that are difficult to analyse using diplomatic and other reporting sources.

Share

The range of forces involved in strategic economic security means that developing and calibrating rigorous policies requires insights from Australian firms, researchers and community groups as well as international partners. Sharing information and insights between these actors can help policymakers harness the distribution of expertise across academia, business and the broader community. This can also help the Australian government build a social license for statecraft initiatives. This is important for community members affected by economic security policies, especially those who may not be closely involved in economic security debates, such as small businesses.

Sharing expertise from a core government group with existing and emerging external nodes also reinforces environment scanning. This is achieved by picking up overlooked insights and providing firms and individuals with an understanding of Australia’s geopolitical interests, its economic statecraft capabilities, and pathways to give feedback on initiatives.

Sharing recommendations:

- Maintain links between the government nodes and external nodes working on economic security. An example of how external nodes could work more expansively with a core government group is on issues like Australian sanctions, which involve Australian firms that must comply with sanctions and the legal entities that help them do this, as well as insights from researchers into the design and effects of sanctions and unintended consequences.

- Share experiences with global leaders in strategic economic security policymaking like Japan, which defines its statecraft vision in terms of carrots and sticks across domains. For example, Australia can learn from Japan’s experiences in standing up an economic security group in its National Security Bureau and in finding ways to integrate the range of modern economic statecraft activities across government. This would dovetail with increasing security cooperation between Australia and Japan and potential economic links in energy, aid and investment initiatives.80

Shape

Shaping decisions of individuals, firms and other states to advance Australian interests should be the ultimate output from a strategic economic security effort, working off linked-up government and external nodes to scan for risks and opportunities in global resource flows.

By evaluating Australian capabilities and the opportunity costs of policies, strategic economic security policy options would include measures to retain and improve overall Australian capabilities as well as ground-floor investments in powerful new tools like international economic data tracking and analysis.

Shaping decisions of individuals, firms and other states to advance Australian interests should be the ultimate output from a strategic economic security effort, working off linked-up government and external nodes to scan for risks and opportunities in global resource flows.

Shaping recommendations:

- Scope policies to use Australia’s attractive labour market — a function of its domestic economic assets and geography — and higher education system as a persuasive carrot in the South Pacific and parts of Southeast Asia at a sustainable rate. These tools may meet the powerful carrot criteria: net economic benefit for Australia and a development accelerator through its effects on incomes, education and skills.81

- Use a strategic economic security framework to navigate difficult policy problems involving global resource flows. For example, the playbook presented in this report highlights that economic connections with China revolve around its position as a net energy importer, its real economy heft, and its policies that shape how resources flow into and out of China, including ideas and information. Focusing on resource flows can help Australia identify those resource flows which offer opportunities to shape decisions in Beijing both directly (like in energy markets) and in groups (like in standard-setting). Through rigorous mechanisms like the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB), Australia already benefits from identifying those investment flows with risks that outweigh the benefits, taking the range of opportunity costs into account.82 This playbook also helps identify the economic buffers that can help smooth out economic shocks like sanctions (and other shocks) that affect individuals and groups - like a social safety net, open markets, multilateral rules and strong public institutions.83

- Expand broad-based research incentives, like Australian Research Council (ARC) centres of excellence, that have delivered exquisite knowledge capabilities in areas like health and biotechnology, quantum, and AI, which boost Australian capabilities and strategic heft.84

- Consider changes to Australia’s international development program to more clearly encompass both short and long-term policy objectives. This could include innovative aid ideas like a two-track approach: one track focused on developing stable long-term environments and the other on key shorter-term economic and geopolitical goals like limiting China’s military power expansion in the South Pacific.85

- Jointly consider policy options that send credible signals of Australia’s longer-term capacity to drive energy transitions (through raw renewable energy exports) and food security (through foodstuffs) across the South Pacific and Southeast Asia by investing early in public goods to help deliver these exports, like sector-specific research grants and infrastructure.86

- Ensure that policies that boost Australia’s productivity, which augments its overall capabilities, are included on the strategic economic security agenda. For example, helping Australian workers adjust to changes in technology through training and education initiatives will help mitigate economic security risks and position Australia to seize international economic opportunities.87

- Work with the United States over time to complement its current ‘small yard, high fence’ de-risking approach with enduring carrots that resonate in the region — like market access for Southeast Asian nations and beyond — to help incentivise coordination to shape decisions in both countries’ interests. In a world where emerging and middle powers vary in alignment on economic security and other geopolitical issues, US carrots will help balance the effects of China's key role in supply chains. US carrots can also help offset the unintended effects of US sticks that draw other states closer to China through economic ties.88 Partners like Japan will be important in efforts to work with the United States on weighing up the power of such carrots against domestic constraints.89

- Evaluate and coordinate sticks with other countries to help deter bad actors or provide off-ramps to undesired geopolitical outcomes. Sticks can serve a range of purposes both economic and non-economic. But sticks can be counterproductive and Australia should work with partners like the United States and through groups like the G7 to limit the use of sticks and, where applied, make them removeable, scoped for value and reduce unintended effects.90

Conclusion

This report has argued that economic security is not new — but managing the risks and opportunities of global economic exchange in a dangerous and interconnected world is at the forefront of policymakers’ minds today. Australian leaders are confronted with tough decisions that require weighing up the value of deepening security relationships against policies that drive Australian economic capabilities and prosperity.

A proactive and long-term approach, like the one proposed in this report, will help policymakers address economic security challenges and seize opportunities that will move Australia towards a more secure and prosperous future.

To help Australian policymakers navigate these tough decisions, this report defines economic security and delivers a robust playbook and practical steps to embed a strategic approach to making economic security policy. The policymaking process outlined in this report can deliver the nuance and clarity that policymakers need to manage economic security issues now and in the future.

Australia will face challenging economic security issues in the years and decades ahead. A proactive and long-term approach, like the one proposed in this report, will help policymakers address economic security challenges and seize opportunities that will move Australia towards a more secure and prosperous future.

Appendix

Shaping decisions using economic tools91

| Economic forces | Non-economic forces |

Market characteristics (including hierarchies, global distribution, elasticities of supply/demand, drivers of innovation, sophistication, role of firms) Market characteristics can be key to understanding who is affected by economic security policies and how they are affected. Examples:

|

Images, Indicators, Commitment, Risk (including altering perceptions of capability/intent, projecting credibility, brinkmanship) For example, a country can use foreign aid or a free trade agreement to signal a commitment to friendly relations with other states and to signal its commitment to promoting economic development in other countries. Conversely, sanctions can be used to demonstrate that future actions from another state will be punished. |

Unilateral or non-unilateral (for example, multilateral, regional and minilateral) tools Depending on the policy goals, countries may want to use unilateral or non-unilateral tools for different effects. For example, evidence from East Asia92 over the late 20th century — when the region was a large user of multilateral freer trade tools — largely supports the argument that economic growth is stronger when multilateral freer trade policies (carrots) are used compared to unilateral freer trade policies. |

Biases, Noise and Perception (individual or group responses to economic statecraft vary) For example, loss aversion is the psychological tendency to care more about losses than equivalent gains. This means that in some situations, bargaining using economic carrots (which can be taken away) is more powerful than bargaining with sticks (which are harder to undo). |

Production, Consumption, Growth For example, remittances from temporary migrant workers can increase the spending power of those individuals and their families, often leading to higher consumption and sometimes higher levels of physical or human capital. |

Politics, Culture, Regional, Historical and Social dynamics (including domestic politics and regional perceptions) For example, apartheid-era sanctions were supported by anti-apartheid leaders in South Africa because foreign pressure on the government was seen to be politically useful. This was despite the economic cost of the measures to some black workers. |

Physical links (including latency, network features, costs, leaks, capacity, transparency) A range of physical links between states exist: goods may be transported by land, sea or air freight; people move between states to buy or provide services using land, sea, and air transport; and information and ideas may be transmitted digitally using airwaves, satellites and undersea cables. |

|

Demography, Environment, Technology For example, US environmental policy goals to increase domestic renewable energy production have been in tension with the goals of US economic statecraft efforts to reduce reliance on goods from China, the major global producer of renewable energy goods. |

Source: Helen Mitchell, Modern Economic Statecraft Framework, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4548008