Executive summary

- China’s use of coercive statecraft is the greatest short-term threat to Australia’s security. Beijing’s grey-zone tactics — ways and means to coerce a country short of the use of conventional force — are used to identify vulnerabilities and set favourable military conditions to its benefit should a conflict eventuate involving the United States, Australia and other allies and partners.

- Not all of Beijing’s grey-zone actions have a military dimension, but novel military and paramilitary effects are a central tenet of its coercion campaign. Though awareness about the nature and application of these is growing, Canberra’s defence planning remains primarily concentrated on traditional military capabilities and force posture. With the advent of AUKUS and increasing US military presence in Australia, Beijing is likely to step up its coercive efforts against Canberra, including by pursuing a military foothold in the Pacific.

- As part of ambitious and active statecraft, the Australian Defence Force (ADF) must embrace new conceptual, operating and capability ideas, underpinned by new teaming behaviours with the National Intelligence Community (NIC) and regional military partners. Focused on Southeast Asia and the Pacific, these efforts would deny the military dimension of China’s coercion while preparing Australia’s own latent advantages for possible future crises or conflicts. This approach will challenge traditional machinery of government design and orthodox conceptions about how military power is applied, especially in clandestine and covert ways.

- Five principles should inspire a diversified Australian military approach to regional grey-zone challenges: imagination and creativity; reducing and offsetting risk; potential for integration; the power of partnerships; and seizing the initiative. Using novel military effects to impose costs and dilemmas against China’s coercive statecraft can accord with Australia’s democratic ethos, scrutinised by robust oversight.

“…if you want to both defend yourself and, on occasions where your interests are engaged, seek to prosecute action in that ambiguous grey-zone, you need to think like those who are becoming accustomed to employing grey-zone tactics. We have to think grey if we’re to effectively respond to grey in the ways that [are] suitable for us and appropriate for the nature of our democracy and values.”General Angus CampbellChief of the Defence Force, 2 July 2020

Policy recommendations

To counter China’s coercive statecraft, Australia should adopt an active military approach in the grey-zone focused on Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Through Australia’s 2024 National Defence Strategy, this can be pursued by the following ten recommendations:

Deepening partner advantages

- Deepen the ADF’s regional military-to-military intelligence relationships through an intelligence diplomacy approach.

- Help regional militaries defend their sovereignty against grey-zone tactics through partner-specific, high-value and enduring security force assistance programs.

- Work with regional militaries to foster new multilateral engagement approaches that strengthen collective resilience in the face of continued grey-zone challenges.

Unorthodox initiative

- Develop a new ADF-NIC integrated operating concept for unpredictable and asymmetric military effects.

- Establish an integrated ADF-NIC operational platform, held at the strategic level, to aggregate and employ intelligence, information and irregular capabilities.

- Build new ADF capabilities to apply unpredictable and asymmetric effects, adapting and learning from proven allied and Ukrainian examples, and which move past legacy special forces thinking.

- Enact a positive legal framework for military-purpose clandestine and covert activities outside of conflict, assured by a robust and legislated oversight mechanism.

Competing overtly

- Establish an Australian ‘white hull’ coast guard to counter-coercion and protect sovereignty at sea.

- Develop standing ADF rapid response options, designed for crisis and shaping missions, to reinforce regional partners and demonstrate resolve in the face of grey-zone aggression.

- Educate and inform public understanding about what China is doing, and the risks to Australia’s security and prosperity, through attribution and exposure.

Introduction

China’s aggressive militarisation of the Indo-Pacific is the principal medium-to-long-term threat to regional order and Australia’s interests. As Australia’s 2023 National Defence Statement argues, China’s large-scale conventional military build-up, combined with rising tensions, is increasing the risks of military escalation and miscalculation.2 With Australia’s 2023 Defence Strategic Review emphasising the end of ten-year conflict warning time, the Albanese government is rightly seeking more potent deterrent capabilities and accelerating preparedness. Canberra’s defence strategy, however, still risks losing sight of current and emerging grey-zone risks which could yield China the benefit of strategic surprise or tactical gains in a future crisis or conflict.

This report contends China’s coercive statecraft is the greatest short-term threat to Australia’s security. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is invoking all elements of national power — party, military, government, civil society and industry — to advance its political and strategic objectives in a global campaign. Nested within this, Beijing’s grey-zone tactics are central to advancing its deeper military objectives. These tactics identify an opponent’s vulnerabilities and create access within target states to set favourable military conditions should a conflict eventuate with the United States and any of its allies or partners. Short of conflict, grey-zone tactics establish a foundation to pursue hybrid warfare or crisis escalations. In Western military thinking, Beijing’s grey-zone actions are redolent of an operational preparation of the environment (OPE) or advance force operations (AFO) campaign. Though not all facets of Chinese coercion have a military objective, seeking military advantages through a ’winning without fighting’ approach accords with historical Chinese strategic and operational art — and thus illuminates the CCP’s true rationale.

Awareness of China’s grey-zone tactics is growing across the region, including in Australia. Beijing’s actions continue to confound democratic, rule-of-law nations like Australia, however, because China’s doctrine of civil-military fusion is so antithetical to the war-and-peace binary.3 Compounding this is the way in which liberal democracies organise their societies and governments: for instance, clearly distinguishing between the public and private spheres, or rigidly stove-piping and separating organisational behaviours between political, diplomatic, military, intelligence, police and economic spheres. In capitals like Canberra, proposing cross-cutting policy innovations that usurp traditional bureaucratic designs and resourcing is still extremely fraught, particularly on vexed issues such as counter-coercion. Herein lies a key strategic vulnerability that Beijing exploits against Canberra: Australia’s democratic strength — girded by laws, norms, morals and ethics — nevertheless makes it comparatively slow to respond. As the Solomon Islands’ 2022 accession to a secretive security pact with Beijing attests, the CCP is a nimble adversary capable of winning influence and access in Australia’s near-region, even in the face of ostensibly proactive policy initiatives like the former Coalition government’s Pacific Step-Up.4

In the past five years or so, Canberra has taken several powerful actions, including world-leading foreign interference laws, the banning of Chinese telecommunications firms from Australia’s 5G networks and, most recently, considerable new investments in Australia’s offensive and defensive cyber capabilities.

Australia’s approach to China’s grey-zone coercion is beginning to turn. In the past five years or so, Canberra has taken several powerful actions, including world-leading foreign interference laws, the banning of Chinese telecommunications firms from Australia’s 5G networks and, most recently, considerable new investments in Australia’s offensive and defensive cyber capabilities. Since its election in May 2022, the Albanese government has moved quickly to address Australia’s regional influence deficit, returning nuance to diplomacy, embracing credible climate and development policies, and pursuing innovative bilateral compacts like the Falepili Union with Tuvalu.5 It has increased Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) funding.6 It has also begun thinking deeply about strengthening Australia’s democracy to withstand political warfare and bolstering Australia’s national resilience to withstand complex, cascading crises.7

On defence matters, however, cause for concern persists. While recognising that China is “engaged in strategic competition in Australia’s near neighbourhood,” the 2023 Defence Strategic Review concentrated primarily on traditional military capabilities and force posture arrangements.8 Consideration of Chinese grey-zone coercion was seemingly minimal and oblique, at least publicly.9 Though the former Coalition government accepted grey-zone activities as a major security threat in policy, Defence Department and ADF structures were not cohered towards continuous campaigning-in-competition and systemic moral and cultural failings in special forces were not adequately addressed. The Australian Signals Directorate’s (ASD) REDSPICE ten-year transformation program was the notable exception,10 yet this conveyed a misnomer that grey-zone is solely a cyber challenge and led to the cancellation of the long overdue MQ-9 Reaper unmanned aerial system.11

Central idea

This report12 argues Australia should adopt an active military approach in the grey-zone, focused on its Southeast Asian and Pacific strategic geography. Contributing to ambitious statecraft, the intent is to deny in competition while preparing advantages for possible future crises or conflicts. Identifying and countering China’s grey-zone actions is the short-term priority. Building asymmetries to impose costs and dilemmas upon adversaries, and generating the novel military capabilities necessary to do so, is the medium-to-long-term objective.13

Ahead of 2024’s first biennial National Defence Strategy, this report seeks to catalyse new thinking about how the ADF can realise this as part of a “unifying national strategic approach.”14

From a practitioner viewpoint, this report asks how new thinking and behaviours can expand Australia’s competitive options and create advantages. Five underlying principles guide the report’s thinking:

- Imagination and creativity: Australians are innately optimistic, curious and easy-going, with a good sense of humour. These attributes encourage bold thinking.

- Reducing and offsetting risk: Actively competing and deterring China below the threshold of armed conflict is cheaper in blood and treasure, and incurs less risk of kinetic action than actual war. Novel military capabilities diversify and expand options relative to signature, hard power means, at a much cheaper cost.

- Potential for integration: Developing new operating ideas, teaming behaviours and capabilities with NIC partners is how the ADF can maximise its unpredictable and asymmetric military power. Integration is how the ADF can cultivate trust and confidence to assure that it can apply and protect sensitive tradecraft.

- Power of partnerships: Australia cannot deter China alone. Longstanding regional military and security relationships can be quietly re-focused for mutual benefit. For Australia to help to defend partner nations’ sovereignty against coercion respects and strengthens those countries’ agency, demonstrates resolve, and contributes to collective deterrence.

- Seizing the initiative: Australia’s democratic ethos is an enduring strength. It enables the pursuit of unpredictable and asymmetric military effects that are just, legal, moral and ethical — upheld by robust and transparent oversight.

Three headline assumptions drive the proposals offered:

- China will continue to escalate and intensify its coercion. Beijing’s recent attempts to economically coerce and politically isolate Canberra have, so far, failed to achieve their objectives.15 Yet Australia’s staunch resistance is likely to invite sharper retaliatory grey-zone challenges going forward. The decision to acquire nuclear-powered attack submarines through AUKUS, expanded US-Australia force posture initiatives and increased ADF regional presence will probably attract more sophisticated OPE/AFO actions. In the Pacific, China will likely seek military basing or access, and deploy coast guard, militia, and civil maritime elements as a means of pressuring Australia ‘in the grey’ on its eastern flank.16

- Sufficient political will exists in Canberra. The 2023 Defence Strategic Review called for focused urgency and argued that business-as-usual approaches to policy development and risk management are no longer adequate.17 Yet employing novel ADF approaches to grey-zone challenges could result in exposure or embarrassment to Australia at some point.18 Current and future Australian governments — and their leaders — must accept and be prepared for this in advance.

- ASIS, ASD and ASIO are willing to embrace integration for military effects. The scale of Australia’s strategic challenge means that every agency and department has more to do than ever in the pursuit of the national interest. Facing sophisticated Chinese actors empowered with cutting-edge technology, novel ADF capabilities will necessitate the kinds of advanced tradecraft traditionally associated with the NIC in order to be successful.19 This is about building ADF advantages, not encroaching upon NIC mandates. Uplifting ADF skills and capacity to operate in the grey-zone will significantly free up NIC capacity for harder and higher-risk intelligence targets.

It is important to note that this report canvasses topics usually absent from credible open-source debate. Inevitably, some context may be missing due to security considerations. But secrecy cannot be a reason to eschew sensitive policy or capability questions, nor can it be an excuse to avoid scrutiny or resist urgent change imperatives from recent failures.

The report is structured around ten policy recommendations, organised into four parts. The preface offers a practical definition of grey-zone activity and key military-strategic terms, and offers a baseline for understanding China’s conception of the grey-zone. Part A considers options for the ADF to pursue as part of deepening its military and security partnerships in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Part B promotes unorthodox options that will require deeper integration between the ADF and NIC and challenge the conventional wisdom in the ADF’s existing special forces capability. Part C lays out several overt ways to expand the ADF’s competitive grey-zone options.

Preface: Locating the grey-zone

Not all facets of competitive statecraft have a military dimension, but novel military effects are a central tenet of grey-zone challenges

The grey-zone

Much has recently been written under the rubrics of grey-zone, political warfare, hybrid warfare, liminal warfare, winning without fighting and active measures.20 Though this literature has proven influential in sounding the alarm, this report is not concerned with identifying the problem; its focus is on how the ADF should counteract the ambiguity and attribution dilemmas characteristic of China’s grey-zone activities and which have serious consequences for Indo-Pacific stability. Not all facets of competitive statecraft have a military dimension, but novel military effects are a central tenet of grey-zone challenges, orchestrated with diplomatic, intelligence, economic and development aspects of national power.

In policy terms, Canberra’s 2020 Defence Strategic Update (DSU20) defined “grey-zone” as:

One of a range of terms used to describe activities designed to coerce countries in ways that seek to avoid military conflict. These tactics are not new, but they are now being used in Australia’s immediate region. Grey-zone activities are being integrated into statecraft and applied in ways that challenge sovereignty, shared interests and habits of cooperation. This includes challenges to long-established and mutually beneficial security partnerships Australia has with many countries, including in the Indo-Pacific.21

In opposition, Labor accepted DSU20’s strategic policy settings. In office, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence Richard Marles has argued that the “binary divide between war and peace” no longer exists and that “the grey zone of contest is much larger today than at any point in history.”22

Simple language

In the Australian context, some terms, such as ‘special operations’ and ‘special forces,’ have arguably become loaded and too narrow. This report invokes different, simpler language –unpredictable, asymmetric23 and advantage — to convey a simple yet compelling idea: the capacity to surprise by operating outside the military norms of the current time.24

Drawing from this, three terms are commonly used throughout this report for simplicity:

| unpredictable | Seeks to: (1) re-frame traditional organisationally-defined boundaries between intelligence and military disciplines; and (2) inside the military, de-construct conceptual rigidities between conventional and special forces. |

| asymmetric | “Asymmetric warfare” refers to military actions that pit strength against weakness, at times in a non-traditional and unconventional manner, against which an adversary may have no effective response. In cost imposition or denial, “asymmetric” refers to the application of dissimilar capabilities, tactics or strategies to circumvent an opponent’s strengths, causing them to suffer disproportionate cost in time, space or materiel.25 |

| advantage | Preparing an operational environment to create conditions conducive to the success of current or possible future military operations. The purpose is to mitigate risk, expand available options, and enable successful follow-on operations. In Western military doctrine, analogous to theatre-setting or special operations forces-centric operational preparation of the environment concepts. |

Other definitions

There is often definitional inconsistency in discussions on irregular military concepts, even among irregular forces themselves. These offer a basis for common understanding within this report.

| special operations | Military activities conducted by specially designated, organised, trained, and equipped forces using distinct techniques and modes of employment.26 |

| special forces (SF) | Specially selected military personnel, trained in a broad range of basic and specialised skills, who are organised, equipped and trained to conduct special operations.27 In ADF service, existing SF are considered to be the Special Air Service (353) and Commando (079) employment categories. |

| operational preparation of the environment (OPE) | Umbrella term to describe actions taken by, or in support of, special forces to develop an operating area and create conditions conducive to the success of a full-spectrum of current or future military operations. These mitigate risk, expand options and enable successful follow-on operations.28 |

| advance force operations (AFO) | Operations conducted to refine the location of specific, identified targets and further develop the operational environment for near-term missions.29 |

| clandestine | Activity planned and conducted to ensure secrecy or concealment. Emphasis is placed on concealment of the activity rather than concealment of the sponsor’s identity.30 |

| covert | Activity planned and conducted to conceal the identity of, or permit plausible denial by, the sponsor. Emphasis is placed on concealment of the sponsor’s identity rather than concealment of the activity.31 |

| unconventional warfare (UW) | Activities conducted to enable a resistance movement or insurgency to coerce, disrupt, or overthrow a government or occupying power by operating through or with an underground, auxiliary, and guerrilla force in a denied area. It includes guerrilla warfare and other direct offensive, low-visibility, clandestine or covert operations, as well as the indirect activities of subversion, sabotage, intelligence activities, and evasion and escape.32 |

Chinese grey-zone thinking

There are several important differences between Western and Chinese military thought. Rather than the defender of the nation, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) is first the armed force and defender of the Chinese Communist Party. In other words, the PLA’s primary mission is the defence and preservation of the party, not the Chinese state itself. Another important difference is the Western military bias towards hard power capabilities and tactics. Western contemporary debate is replete with anxiety about DF-27 missiles, PLA-Navy (PLA-N) aircraft carriers and J-20 fighters. Meanwhile, Chinese military thinking elevates narrative and political influence as the preeminent battlefields to contest. Yet a broader understanding and consideration of “discursive power,” “united front work” and “international liaison work” has failed to penetrate allied military thinking.33 This severely impacts the cogency of allied strategy, force design and operational plans against a Chinese military adversary.

Beijing’s grey-zone is not a new concept. The PLA’s capstone doctrine, the Science of Military Strategy, posits that the boundaries between peace and war are vague.34 For the PLA, this necessitates deeper military-civilian integration and joint integrated attacks to widen the military strategic spectrum. Legally, the revised 2020 National Defence Law included new authorities for the “defence of other security domains” beyond border, coastal and air defence.35 Organisationally, the CCP uses an extensive mosaic of ‘action arms’ to execute its strategic and military objectives. Most do not have a natural analogue in Western governmental design. Many of the methods and tactics used do not legally or conceptually fit with normative Western views which traditionally separate political, military, intelligence, security, police, diplomatic and economic spheres.

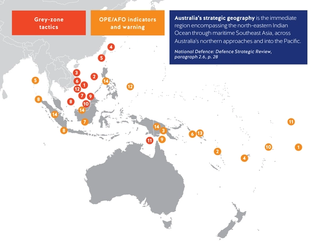

Figure 1. Selected Chinese grey-zone actions

Not all Chinese coercive statecraft has military consequence

Actions of relevance to other arms of government and wider society

|

Actions of military interest

|

| Map | Target/where | When | What |

| Grey-zone tactics | |||

| 1 | South China Sea | Ongoing | Island reclamation and military base construction at Woody Island, Fiery Cross Reef, Mischief Reef and Subi Reef |

| 2 | Philippines (West Philippine Sea) | Ongoing | PAFMM swarming and saturation tactics backed by CCG intimidation and harassment |

| 3 | Vietnam | Ongoing | PAFMM ramming Vietnamese fishing boats |

| 4 | Japan | Ongoing | Incursions into air defence identification zone around the Senkaku Islands |

| 5 | Taiwan | Ongoing | High-volume incursions into air defence identification zone |

| 6 | Vietnam | 2019 | Harassment and intimidation of energy exploration activities inside Vietnam’s EEZ by China Geological Survey ship, Haiyang Dizhi 8 |

| 7 | Malaysia | 2020 | China state-owned survey ship loitering in EEZ, protected by CCG/PAFMM |

| 8 | Indonesia | 2021 | CCG EEZ harassment around Natuna Islands |

| 9 | Malaysia | 2021 | PLA-AF tactical flight formation harassing Kasawari gas field construction |

| 10 | Malaysia | 2021-2022 | Cyber attacks against companies operating in the Kasawari gas field |

| 11 | Australia (Arafura Sea) | 2022 | PLA-N offensive use of a military-grade laser against RAAF P-8A |

| 12 | Australia (South China Sea) | 2022 | Aggressive, unprofessional flying by PLA-AF J-16 against RAAF P-8A, including dispensing of flares and chaff at an unsafe distance |

| OPE/AFO indicators and warning | |||

| 1 | French Polynesia | 2018 | Chinese $2 billion fish farm at Hao atoll, adjacent to former French military nuclear test base and runway |

| 2 | Vanuatu | 2018 | China canvasses military access rights |

| 3 | Papua New Guinea | 2018 | Chinese interest in ports at Wewak, Kikori, Vanimo and Manus Island |

| 4 | Fiji | 2018 | China interest in funding Blackrock camp |

| 5 | India | 2019 | Chinese vessel Shiyan-1 found carrying out research activities inside EEZ; expelled by the Indian Navy |

| 6 | Solomon Islands | 2019 | Lease of Tulagi island sought by Chinese SAM Enterprise Group with exclusive rights over a 75-year period |

| 7 | Indonesia | 2021 | Illegal undersea glider drone incursions near South Sulawesi |

| 8 | Indonesia | 2021 | Chinese survey ship Xiang Yang Hong 03 ‘running dark’ in territorial waters around Lombok Strait and Indian Ocean |

| 9 | Papua New Guinea | 2021 | Hong Kong-registered company plan to build a “multi-billion dollar city” on Daru Island, 200km from Australia |

| 10 | Samoa | 2021 | Chinese plan to develop port at Vaiusu Bay; cancelled by Samoan Government |

| 11 | Kiribati | 2021 | Chinese approach to upgrade runway on Kanton island |

| 12 | Palau | 2021 | Chinese survey ship Da Yang Hao accused of illegal activities in Palau EEZ |

| 13 | Solomon Islands | 2022-2023 | Continued Chinese state company interest in ports and airfields, including Honiara and Kolombangara Island |

| 14 | Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea and Philippines | Last five or so years | Active operations by Chinese private security companies, including Frontier Services Group, China Security and Protection Group, Chinese Overseas Security Services and Hanwei International Security Services |

Part A: Deepening partner advantages

How the ADF and its Southeast Asian and Pacific partners, together, can compete against grey-zone tactics, resist coercion and create future advantages

1. Deepen the ADF’s regional military-to-military intelligence relationships through an intelligence diplomacy approach.

To prepare for its core purpose — conflict and crisis — the ADF needs its own robust and habitual relationships with regional military intelligence counterparts.36 With reduced strategic warning time, the ADF needs an ‘intelligence diplomacy’ approach that deepens liaison relationships, opens new access and, over time, builds confidence towards possible, more intensive future military challenges.37 This runs much deeper than just exchanging information. When surprise moments ‘come out of the blue,’ former ASIS Director-General Paul Symon argued in 2020 that intelligence diplomacy and liaison relationships ensure Australia ‘can continue or build on a conversation that [it has] already built up over many years.’38 Applied militarily, with a long-term mindset, this approach can strengthen partner resilience and create future operational advantages.

Problematically, the ADF is not generally thought to undertake regular and routine intelligence liaison outside of Five Eyes arrangements. National agencies hold the authority and mandate in peacetime to lead bilateral intelligence relationships — and rightfully so — as military requirements assume lesser priority against diplomatic, economic and other security interests. Several military-related liaison relationships exist through the Defence Intelligence Organisation,39. But during the post-9/11 era, counter-terrorism priorities superseded the military imperative to reciprocally traverse sensitive matters in the absence of an exigent state-based threat. Another contributing factor is that the ADF has seldom been an owner or originator of raw intelligence.

Pursuing combined collection activities with some select partners, such as Indonesia, Singapore and the Philippines, is a viable, deeper aspiration.

Yet China’s military aggression is providing the mutual impetus for change, across both NIC-ADF and ADF-regional partner contexts. ADF intelligence diplomacy as such, conducted through the Chief of Defence Intelligence,40 should establish regular military-related information exchanges and sensitive operational discussions, as routine. Pursuing combined collection activities with some select partners, such as Indonesia, Singapore and the Philippines, is a viable, deeper aspiration. Practically, this approach ought to pursue three new areas of cooperation by:

- Sharing more intelligence than presently occurs. Amidst probable Chinese diplomatic pressure, Australia’s regional partners will want to see clear dividends from hosting increased ADF intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) presence. Indeed, Australia already operates advanced ISR and maritime domain awareness assets from regional operating locations in Malaysia, the Philippines and Singapore,41 including platforms such as the P-8A Poseidon,42 E-7A Wedgetail43 and Collins-class submarine,44 and in coming years, the MQ-4C Triton,45 MC-55A Peregrine46 and the ship-hosted Surveillance Towed Array Sensor System-Expeditionary.47 Expanding the aperture for sharing intelligence gathered by these platforms should be a priority. Offering tactical and operational-level insights into PLA capabilities and their tactics, techniques and procedures gleaned from overt ADF actions provides a safe start-point for collaboration while positive sharing protocols develop and mature. Beyond informing awareness and understanding, increased sharing can directly influence the way that recipient forces defend their nation’s sovereignty against grey-zone tactics. ADF intelligence feeds could enable tipping or cueing of targeted counter-actions developed through other capacity-building efforts (see policy recommendation two), tangibly investing confidence that Australia is a reliable and credible partner.

- Offering advanced training, collection equipment and analytical tools. These would complement NIC activities, be tailored bilaterally and be subject to case-by-case policy approval. Military cooperation could be selectively expanded within human, signals, geospatial and all-source analytical intelligence disciplines.48 In some instances, the ADF would assume operational lead, like reported ASIS airborne signals intelligence support to the Armed Forces of the Philippines or tradecraft provision to Japan.49 For others, like Singapore, who already possess sophisticated capabilities, the ADF could support their collection activities and demonstrate reciprocal potential for more advanced, harder target problems. In each possibility, ADF personnel could mature routine linkages with counterpart analysts and collectors, representing a leap forward in engagement compared to the present. Capability exposure trade-offs notwithstanding, empowering partners’ intelligence collection offers the ADF valuable access, redundancy and deniability gains over the long run.

- Deploying permanent ADF intelligence liaison officers across the region. In-person presence will be essential to normalise new sharing behaviours and facilitate real-time exchanges when opportunities or crises emerge. Security requirements and limitations in classified information technology will practically dictate this. To share an ADF-originated classified report, for example, it would likely have to be delivered by hand from the Australian diplomatic mission.50 Moreover, Canberra’s military attachés are coordinated by the Defence Department’s international policy division and not through intelligence channels.51 Merely leveraging the existing attaché network (within normal, less secure diplomatic channels) will discourage sensitive cooperation. Investing in trust is the greater sine qua non. Trust in intelligence may be eternally elusive, but should be vigorously pursued — and towards ADF purpose — as a pathway towards more complex, future military scenarios and risks.

For any deeper engagement pursued, Canberra will need to consider new ways to enable and protect increased classified military information sharing with regional partners. Unlike its Five Eyes bonds, and to a lesser extent with NATO, Australia does not historically enjoy a trusted security culture to safeguard classified information sharing with regional friends.52 Though steps with Singapore and Japan are well underway, these do not rival the maturity and depth between the Five Eyes partners.53 Amidst aggressive Chinese intelligence and cyber threats, developing ways to inculcate stronger operational security discipline with partners will be an intensive endeavour demanding considerable patience.54

Legally, new bilateral agreements may need negotiation, particularly in Southeast Asia. Existing intelligence legislation and ministerial direction may not cover or sufficiently protect ADF-generated and released information. Increased sharing will generate more case-by-case policy and process issues, both within Canberra and for its allies. Bigger intelligence loss/gain, technology exposure and security themes will necessitate a sizeable, dedicated foreign release policy staff. Increased cooperation will also raise longer-term desires for classified data, voice, and video connectivity, particularly for senior-leader engagement, analogous to US-delivered multinational CENTRIXS networks.55 Alone, a legal agreement or bespoke communication network does not foster mutually trusted processes and sharing cultures. Canberra must genuinely innovate if it wants to ‘deepen its engagement and collaboration’ with regional partners.

Table 1. Military-to-military intelligence

Examples illustrating how ADF Intelligence Diplomacy could help invest confidence that Australia is a credible and trusted partner

| Sharing more Action: Enable tipping or cueing of targeted counter-actions developed through other capacity-building activities Example: ADF shares early warning about planned PLA harassment operations around the Natuna Islands, thereby enabling Indonesian forces (TNI) to defensively posture in advance.56 TNI prepares media exposure actions to reveal PLA grey-zone tactics and enable Jakarta to diminish CCP political claims. |

Advanced cooperation Actions: Advanced collection skill and tradecraft training Provision of specialist collection equipment and analytical software Example: ADF assistance enables the Royal Brunei Armed Forces (RBAF) to build a sophisticated collection platform to target military-related espionage and operational preparation activities in Brunei. Through combined activity, RBAF increases capacity to defend its sovereignty while ADF increases understanding of covert PLA networks in the region. |

Liaison officer presence Actions: Closer relationships with host nation military capabilities, as a lived behaviour, on an enduring day-to-day basis Assurance via secure (Australian) information technology for ADF intelligence and sensitive operational information Example: Habitual ADF Liaison Officer presence builds trust and confidence. In turn, host military offers the ADF permission to collaboratively pursue non-kinetic effects against a target involved in a covert PLA logistics network operating across the region.57 Start-point yields further military-specific intelligence gains and opportunities over several years. |

2. Help regional militaries defend their sovereignty against grey-zone tactics through partner-specific, high-value and enduring security force assistance programs.58

Chinese coercion is creating openings for the ADF to build layered advantages with its regional military partners. Offering bespoke security force assistance programs that address the same vulnerabilities that Chinese grey-zone tactics attempt to exploit can help the ADF foster deeper bilateral linkages with regional partners.59 In the short term, high-value ADF support would strengthen partner resilience and capacity to defend their own sovereignty.60 Over the long run, it would uplift the effectiveness of regional forces and normalise the ADF’s basing access for more complex scenarios.61 This is the natural operational and tactical-level complement to ADF intelligence diplomacy.

To achieve this, small ADF expert teams would embed within a military partner to provide ‘advise, assist and enable’ (A2E) effects.62 Such support would not be publicly declared — both to protect host-nation political interests and operational security, and pose counter-dilemmas against grey-zone actors. The ADF’s grey-zone assistance would apply lessons from recent military and intelligence case studies, anchored by three core principles:

- Partner first, with respect and understanding.63 In practice, this means pursuing a ‘by, with and through’ (BWT) operational approach.64 Premised on real-world challenges, BWT encourages sustained cooperation types that directly support partner needs. Traditional peacetime ADF international engagement is mostly focused on people-to-people exchanges and cultural ties. ADF partnering with the Iraq Counter Terrorism Service (counter-Daesh) and Papua New Guinea Defence Force (APEC 2018 security) followed this approach.65

- High-value support. Assistance would only be agreed upon where partner forces have limited capacity and would be narrow to directly target grey-zone (and latent hybrid) threats. The ADF needs to be adaptive and innovative beyond its existing ‘in-service’ capability solutions, as cutting-edge British technology support to meet Ukrainian requirements demonstrates.66 Australian intelligence and police counter-terrorism assistance in Southeast Asia post-Bali (2001) is an exemplar: sharing specialist operational tradecraft and technology enabled local authorities to disrupt terror networks and plots, such as the targeting of Noordin Mohammad Top, Dulmatin and Santoso in Indonesia.67

- Enduring approach, programmatic delivery. Lasting, robust and sustainable capability should be the goal. Ukrainian intelligence and special operations examples, sponsored by the British and Americans since 2014, prove the dividends possible from sustained, patient and discreet multi-year efforts.68 A short-term rotational deployment model — as the ADF is accustomed to from the Middle East and Afghanistan69 — will not deliver effective counter-coercion assistance. Borrowing from intelligence and counter-terrorism cooperation methods, including in-country postings and longer-duration training delivery in Australia, offers better potentialfor the types of Chinese grey-zone tactics manifest.70

Three headline issues need consideration. Politically, Canberra should expect partners will likely want and ask for more — knowledge, equipment, or in some scenarios, direct parrying of Chinese actors. By way of comparison, ADF combat training is still being provided to the Philippines six years after the Marawi siege.71 Policy-wise, the peacetime Defence Cooperation Program is an inappropriate vehicle for operational effects.72 Inside the Department of Defence, international engagement authorities and administrative controls remain inefficiently divided between the Strategy, Policy and Industry Group, the military services, and Joint Operations Command. The ADF’s theatre commander, Chief of Joint Operations, should unify military grey-zone support to partners, cohered with all other ADF operations, activities and actions.73 In force structure, despite strategic trends over two decades, the ADF does not possess dedicated capability for this role, akin to British 77 Brigade or US Security Force Assistance Brigade examples.74 The ADF readily has the individual expertise and talent to generate this approach if its internal processes can become nimble to adopt intelligence agency-like delivery methods.

Table 2. Grey-zone security force assistance

Examples of how the ADF could offer advise, assist and enable effects, delivered by small five to 15-person teams, embedded at tactical or operational levels of command, with an enduring approach

| Supported capability | Narrative | Precedent |

| Aviation | Support a partner’s small military air wing to strengthen training, airworthiness and availability. Habitual presence leads to improvements, which enable the ADF to donate additional new, commercial-type aircraft, increase partner capacity and introduce new capabilities. | RAAF 35 Squadron and PNGDF Air Transport Wing sister squadron relationship75 |

| Close-target surveillance and reconnaissance | Uplift a partner’s discreet military capabilities to identify and disrupt threat networks conducting military-purpose advance force operations, and illegally operating within their sovereign territory or Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ). | Australian intelligence and police relationships with POLRI Densus 8876 |

| Maritime security | Support a partner military or coast guard to innovate and experiment with ways to counter and disrupt grey-zone tactics, including through rapid acquisition and employment of novel commercial technologies, to defend its maritime sovereignty. | UK materiel support and special forces cooperation to Ukraine77 SOCOMD Innovation and Experimentation Group |

| Higher-level command and control (C2) and operating concepts | Help develop a partner’s capability to command and control joint operations with increased situational awareness and operational security. Evolve to help plan a menu of asymmetric defensive options should China vertically escalate to a hybrid warfare campaign. | US ‘porcupine’ strategy planning assistance to Taiwan |

3. Work with regional militaries to foster new multilateral engagement approaches that strengthen collective resilience in the face of continued grey-zone challenges.

New multilateral military engagement approaches in Southeast Asia and the Pacific are needed, practically orientated to common challenges. Amidst continued Chinese coercion and aggression, this approach pursues dialogue, understanding and cooperation to achieve shared goals and invest in collective security. The ADF has the experience to successfully establish such initiatives, drawing upon its longstanding regional relationships, engagement acumen and multilateral participation elsewhere. However, the ADF cannot build these alone. From the outset, shared ambition and leadership from other regional militaries is essential to ensure cultural respect and genuine buy-in.

In Southeast Asia, a military cooperation centre against irregular threats would help build resilience — institutionally within each participant force, and regionally towards collective security.78 Inspired by the Jakarta Centre for Law Enforcement Cooperation (JCLEC) model, its mandate would build capacity for maritime security, grey-zone, and hybrid and resistance warfare scenarios.79 Its potential lies in the power of networks: exchanging liaison officers, knowledge sharing and coordination between forces, at lower command levels, who are being targeted by malign Chinese actions. As a liaison and learning hub, it would be anchored by a permanent campus, cadre staff, secure information technology system and senior advisory board. Critically, it would impose a direct cost on Beijing for its coercive campaigns hitherto, while investing in ‘warm-start’ behaviours should a conflict arise.

Practically, Southeast Asian architecture is weak towards military cooperation. ASEAN is hampered by its consensus-based approach and avoidance of difficult issues, such as PLA access in Myanmar and Cambodia.80 Meanwhile, ASEAN Defense Minister’s Meeting-Plus military exercises are superficial and impeded (in an operational security sense) by Chinese and Russian participation.81 Military precedent to engage sub-regionally on complex and sensitive issues does exist, however, and a ‘JCLEC for the grey-zone’ is plausible. The Counter-Terrorism Information Facility, the maritime security International Fusion Centre, and the Southeast Asian Special Operations Commanders’ Conference exemplify this.82 Since 2017, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines have undertaken combined patrolling in the Sulu Sea area against transnational threats.83

Table 3. Southeast Asia military cooperation centre against irregular threats

| Engagement types | Capabilities envisaged | Essential inputs |

| Commanders’ dialogues Individual training and education short courses Knowledge sharing seminars Liaison officer hub Specialist capability enhancements Table-top exercises |

Command and control (C2) Counter-terrorism Information analysis Information and cyber warfare Intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance Maritime security Operational security Unconventional warfare |

Chief of Defence-level

memorandum of understanding Host country for permanent campus Multinational cadre staff Secure information technology Specialist assets and subject matter expertise for short exercises and courses |

In the Pacific, a bespoke ‘Blue Pacific climate force’ should operationalise the 2018 Boe Declaration and its human, resource and environmental security conception.84 For Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) leaders, Beijing’s quest for a regional military foothold is not a first-order issue. Climate change is “the single greatest threat to the livelihoods, security and wellbeing” of Pacific peoples with rising temperatures and sea levels already posing an existential threat to several PIF nations.85 Building collective resilience against increasingly frequent and severe climate disasters could offer Canberra greater political legitimacy to simultaneously pursue its sovereign influence and security goals to undermine China’s grey-zone approach and deny PLA basing access across the region.

The ‘climate force’ idea amalgamates European civil defence and home guard concepts, tailored to Pacific needs.86 Capabilities too intensive or costly for PIF nations to develop themselves become possible through economies-of-scale and external donors. NATO has viably proven supranational force constructs in heavy airlift, aerial refuelling and surveillance capabilities.87 Entry would be open to all PIF citizens, and members would retain their national flag. It would be a disciplined force, under a military-like chain of command, but it would not have offensive roles or capabilities, thereby preserving the region’s mostly non-military security character.

In delivery, the respected Pacific Maritime Security Program offers a mature start-point for Canberra to re-frame and cohere its various Pacific security initiatives towards climate change.88 Alongside ADF leadership, New Zealand, French, Japanese and US militaries could unify their efforts and help to generate the requisite capabilities. The Australian Defence Department’s new Pacific Division would enable finance, contractual and coordination aspects. Basic training and trade skills would be delivered by existing ADF schools. The number of ADF advisors and technical experts based in PIF nations would significantly increase, while expert contributions from Australian fire, ambulance and emergency management agencies would be a multiplier.

Competing against its grey-zone influence, Beijing is confronted with a sophisticated dilemma.89 Why would PIF nations host an offensive PLA base when Australia, and other friendly partners, are supporting their adaptation struggle against an existential threat? Working with the region on climate change mitigation denies China a false binary narrative, leaving PIF nations to make choices foremost based on their security. Australia’s legitimacy and “Pacific family” narrative would be burnished while potentially seeding future advantages in case of hybrid or conflict escalations. It would also weaken arguments for establishing new military forces or facilities in the region, such as in the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, where they currently do not exist (and are arguably not required).90

Table 4. Blue Pacific climate force

ADF-assisted specialist capabilities for human, resource and environmental security issues, generated with economies of scale. Climate change resilience main focus.91

| Pacific Sovereignty Operations Centre |

|

| Maritime |

|

| Pacific Islands Support Regiment89 |

|

| Air |

|

Part B: Unorthodox initiative

New unpredictable and asymmetric military capabilities and effects, generated through integrated ADF-NIC teaming, focused on Australia’s strategic geography

4. Develop a new ADF-NIC integrated operating concept for unpredictable and asymmetric military effects.

Canberra needs to embrace new thinking, actively and quickly, to counter China’s coercive statecraft. This should extend beyond the known or deducible grey-zone tactics of today. It must deny or disrupt the ways China could pursue hybrid warfare or conflict escalations through non-military cover, without detection, achieving surprise, for greater military impact and harm. Illustratively, using commercial shipping to strike or special forces masquerading as foreign construction workers to sabotage rather than missiles from warships or bombers, are simple examples.93

An ADF-NIC operating concept would provide the intellectual basis for new unpredictable and asymmetric military effects in Australia’s strategic geography.94 Contributing to deterrence, expanding clandestine and covert military options to impose costs and dilemmas upon stronger adversaries would be its central idea.95 Policy-wise, it would explain why closer military and intelligence integration is needed while safeguarding against overreach into respective mandates. As a military concept, it would explore how latent advantages could be developed before crisis or conflict ensues;96 and how sovereign grey-zone challenges could be wielded. It would challenge orthodoxies and guide new organisational design, capabilities, policy and legislation. In every aspect, it would leverage whole-of-nation potential and reflect Australia’s democratic, rule-of-law and moral character.97 Above all, it must serve as a clarion call inspiring new mindsets, cultures and teaming behaviours between (and within) the ADF and NIC.

Canberra needs to embrace new thinking, actively and quickly, to counter China’s coercive statecraft.

Such a concept does not exist in the Australian context. The ADF recently published new capstone and Indo-Pacific concepts responding to China’s military expansion, Sino-US competition, and technological and character-of-warfare trends.98 An ADF-NIC operating concept would sit below these in classified and public versions. A public rationale would assist transparency and accountability, potentially endorsed as part of the inaugural National Defence Strategy in 2024. Allied parallels — such as the UK Special Operations Concept and US Irregular Warfare Annex — have been embraced by London and Washington in their national and defence strategies.99

The PLA, officially and through authorised individuals, has signalled extensive interest in alternative forms of military power, such as the “three warfares,” which are heterodoxic to Western military norms.100 The PLA’s latest official Science of Military Strategy doctrine highlights, among others, the importance of “hidden front struggle” and the “magic weapon of disintegration”; the value of “abnormal tactics”; “concealed delivery” and “strategic disguise” in force projection; and the need to “strengthen special reconnaissance and destruction forces” survivability behind enemy lines.101 Commercial attempts to develop dual-use basing infrastructure in the Pacific, covert renditions (including from Australia) and underwater drone reconnaissance in Indonesian territorial waters are all symptomatic of China’s approach to pursuing deeper operational preparation of the environment.102 These add weight to judgements that China will use hybrid methods in a future crisis or conflict to exploit Western complacency.103 In fact, it has already laid many of the grey-zone foundations to enable this approach, such as hidden networks, civilian front companies for logistics and intelligence-style tradecraft.

Besides threat influences, three imperatives should influence an integrated Australian military-intelligence idea.

- Risk. Decision-makers must become more risk-acceptant and demonstrate resolve by taking more calculated risks.104 This does not imply the use of armed force, or illegal or immoral actions. Rather, to become comfortable with using cunning, deception and guile to find and target Chinese vulnerabilities, focused within Australia’s strategic geography, proportionately as part of deterrence.

- Offsetting. Australia remains predominantly focused on signature and exquisite hard power capabilities, creating two major vulnerabilities. Firstly, in time: strategic circumstances are deteriorating faster than many of these can be viably fielded, in number and magazine depth. Secondly, in approach: the ADF is preparing too narrowly for high-intensity conflict and insufficiently addressing the military dimensions of China’s grey-zone tactics. Canberra must ‘think grey’ to offset this imbalance, with urgency, as a cheap mitigation while various missile, submarine and surface combatant projects await delivery.

- Trust. The Brereton war crimes inquiry, severe operational security breaches and continued patterns of irresponsible conduct have, quite rightly, cast severe doubts about the suitability of the ADF’s existing special forces.105 While the ADF has enacted modest changes at the edges, major structural, capability and command accountability questions linger.106 Across political, policy, inter-agency and allied partner audiences, significant transformation remains needed to invite renewed trust that the ADF can undertake sensitive activities, with secrecy, which are legal, moral and accountable.107

5. Establish an integrated ADF-NIC operational platform, held at the strategic-level, to aggregate and employ intelligence, information and irregular capabilities.

New types of creative, multidisciplinary teams will be needed to orchestrate unpredictable and asymmetric military effects. Innovative force structure and machinery of government is essential to generating bespoke teams, tailored for high-payoff effects and complex threat and risk environments. Akin to how the Cold War’s onset established ASIO and ASIS, the Defence Strategic Review’s imperative creates the rare, positive opportunity to realise new organisational, capability, procedural and policy design. This calls for a family of diversified ADF and NIC capabilities, organised, resourced, protected and employed together as a national strategic-level asset through a unified chain-of-command.108 In essence, a 21st century incarnation of the Second World War’s Special Operations Australia, boldly re-imagined in the face of China’s coercive statecraft and opaque military build-up.109

An integrated ADF-NIC operational platform should be established by a combination of executive order, legislative change, and a special prime ministerial directive.110 Its concurrent mission would be to contest grey-zone coercion and prepare future military advantage. Reflecting Australia’s strategic geography, this demands equal investment across the navy, army and air force. Reflecting the adversary’s blurring of operational boundaries, foundational ASIS, ASD and ASIO participation is a conceptual prerequisite. Integration would be achieved in four main ways:

- Organisation. The platform would administratively reside within the Defence portfolio, commensurate with its core military purpose. Home service or agency identities would be maintained. The British National Cyber Force offers a contemporary roadmap of how unified military-intelligence organisational design and teaming can empirically work.111 The Joint Capabilities Group offers a logical home given its emerging fourth ‘purple’ service role and hosting of force-level cyber, information, space and logistics capabilities.112

- Capability. Three functional groupings would provide the platform’s baseline to generate bespoke mission teams. Intelligence would mostly draw from the NIC. Influence would derive from developing ADF cyber and information capabilities. Irregular would build new asymmetric military capabilities and evolve the Army’s existing special forces. These would be enabled by intimate science and technology support, and leveraging whole-of-nation potential, through mechanisms like the nascent Advanced Strategic Capabilities Accelerator to help realise options for generating unique effects.113

- Leadership. A three-star or deputy director-general officer would lead a unified management chain. Other senior roles would be shared and organisationally balanced. A single classified funding line would also simplify the process and help dispel any bureaucratic resistance. Key appointments would be legally permitted to exercise both military and intelligence authorities, for integrated effect, within single operational plans.114 A significant cognitive capability would analytically target and plan effects against adversary vulnerabilities.115 High degrees of operational security and compartmentalisation would protect the platform.116

- Policy. A First Assistant Secretary-level policy adviser would lead whole-of-government policy development. Unpredictable and asymmetric capabilities and effects will invariably invoke higher strategic risks, particularly outside of declared conflict. Balancing ADF-NIC operational viewpoints, this role would ensure that political, diplomatic and legal risks are appropriately considered before options are sent for approval. Ideally, this appointee would be a recent senior ambassador or Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet official.117

Old assumptions and organising behaviours no longer suffice for the blurred operating environment the ADF faces.118 Layered whole-of-government committee processes — designed for a different era and strategic appetite — do not promote flatter, faster and imaginative cross-capability options.119 Rapidly amalgamated, reactively formed teams — like the Douglas Wood or Alfredo Reinado task forces — are unlikely to be competitive for the sophistication of the PLA and its proxies.120 With the erosion of ten-year warning time, political leaders have acted largely through long-term initiatives including the acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines and long-range missiles. Drawing upon the same policy rationale, a combined ADF-NIC platform would offer an integrated capability and operational answer to expand Australia’s competitive options while mitigating vulnerabilities, faster and at a fraction of the cost, relative to hard power.

6. Build new ADF capabilities to apply unpredictable and asymmetric effects, adapting and learning from proven allied and Ukrainian examples, and which move past legacy special forces thinking.

Besides new thinking and teaming, novel military capabilities are practically needed to diversify Canberra’s grey-zone toolkit and prepare future advantages. Realising the ADF’s own unpredictable and asymmetric intent requires greater imagination — and the resolve to challenge and retire legacy special forces thinking.

The obstacle lies in the stewardship of special forces over the past two decades, during which special operations (the concept) and special forces (the capability) ideas atrophied to become army-exclusive, losing their historical all-domain value. Special Operations Command is an Army organisation, contrary to a 2002 Cabinet direction for a joint command and dissonant with leading allied approaches.121 ‘Special operations’ resourcing remains curtailed as a Land-domain program in Defence’s capability system.122

Realising the ADF’s own unpredictable and asymmetric intent requires greater imagination — and the resolve to challenge and retire legacy special forces thinking.

Operationally, over 15 years of post-9/11 counter-terrorism activities mythologised kill-capture missions, and the overuse and misuse of special forces in Afghanistan rendered them synonymous with elite infantry.123 Worse still, the Brereton inquiry and Crompvoets report further revealed toxic exceptionalism and rivalry as plaguing special forces units.124 In all, this context — and the desire to protect tarnished regimental structures and identities — has obstructed new thinking.125 The absence of any special operations or special forces discussion in the publicly available version of the Defence Strategic Review underscores this judgement.

Tailored to Australia’s strategic geography, adversary strengths and technological trends, the following proposals would build new capabilities not found in today’s ADF. They demand resourcing and expertise from all five military domains, create integration options more attractive to the NIC, and broaden avenues to leverage whole-of-nation potential.126 Critically, they offer clandestine-to-covert utility across grey-zone, hybrid and conflict scenarios.127

- An asymmetric maritime capability would pursue advantages in surface, undersea and seabed environments, diversified beyond submarines.128 Harnessing remote and autonomous systems, hiding among the region’s dense maritime clutter and operating vessels-of-opportunity would be key elements. It would leverage the considerable resources and expertise developing through Australia’s naval shipbuilding program and maritime defence industry. Generated by the Navy, its workforce would involve engineering, technical, cryptological and logistical skillsets, complemented by a direct-entry pathway to attract advanced expertise from the civil maritime sector. A frogman or commando-like operator would be a supporting, not primary, skill set.129 Containerised missile systems and below-water line modifications (including for sea mines) offer ways to contemporise the Second World War clandestine auxiliary raider concept employed successfully by the German Kriegsmarine.130

- A close-access collection and effects capability would target the military dimension of Chinese grey-zone actions. Revealing hidden networks, finding hard targets and preparing latent operational advantages would be its long-term remit, as part of an “enhanced integrated targeting capability.”131 It would fuse military-purpose intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance and cyber capabilities with national agency-level tradecraft.132 Intimate collaboration with ASIS, ASD and ASIO would be essential to help train the capability, to generate complementary options beyond their authority or capacity, and to credibly assure their trust and confidence.133 The workforce would be selected for intellectual and technical attributes foremost, expanding avenues for diverse ethnic-linguistic and mature-age demographics. Its talent must maintain cover, uphold operational security discipline and be trusted to operate in isolation over months and years.134 Crucially, this would not be a capability sub-set attempted from martial-skill units.135 Unique American, British, French and Swedish capabilities prove the military value and need.136

- An unconventional warfare (UW) capability, operating through official partners or vetted proxies, should be reprised within the permanent force.137 UW enables a resistance movement to coerce, disrupt or overthrow an occupying power. The Pacific should be Australia’s UW focus, particularly where China actively seeks a military foothold. Competing for influence, deepening networks and building resilience (to prepare future resistance) should be the main objectives.138 UW’s weapon system is the human capital and relationships developed within supported partners or proxies. Army has maintained a modest reserve UW cadre since the mid-1950s, part of which formed a joint capability with ASIS until 1984.139 Army is slowly re-embracing aspects of this past; but an Afghanistan-era, direct action emphasis lacks nuance for the Pacific, and should be intensely scrutinised.140 Explicit policy and resourcing is needed to ensure a focused capability.141 Recruiting Pasifika diasporas within Australia and co-generating aspects with New Zealand warrant exploration.142 Ukrainian insights have illustrated the enduring potential of resourced and rehearsed proxies, Jedburgh-style advisory teams and stay-behind networks.143

Table 5. Applying unpredictable and asymmetric military effects

Illustrative examples of how new ADF capabilities could be used to counter grey-zone actions and prepare future advantages

| Asymmetric maritime Grey-zone (competition) |

Close-access collection and effects Grey-zone (competition) |

Unconventional warfare Hybrid (crisis) |

| Vignette ADF delivers proximal (degrade) cyber effects at sea against Chinese-flagged commercial ships being used as covert signals intelligence collection platforms |

Vignette Long-term ADF human and technical surveillance to find and detect covert Chinese actors and their local agents conducting military-related preparation activities in the Southwest Pacific |

Vignette ADF-controlled proxies conduct sustained, non-lethal sabotage campaign to disrupt covert PLA and PAFMM elements attempting to trigger a security crisis in a vulnerable Pacific nation |

| Basis Russian ocean research ship conducting undersea reconnaissance of seabed electricity cables, gas pipes and wind farm infrastructure in the North and Baltic Seas144 |

Basis Reported UK Special Reconnaissance Regiment low-profile cost-imposition against Russian actors in the Baltic, Syria and Africa145 |

Basis Reported Australian disruption operations against people-smuggling ventures146 |

7. Enact a positive legal framework for military-purpose clandestine and covert activities outside of conflict, assured by a robust and legislated oversight mechanism.

Unpredictable and asymmetric military approaches can be just, moral and ethical. Assuring this requires a positive legal basis to apply unique effects outside of conflict.147 Robust oversight is equally fundamental to sustain the Australian people’s trust and uphold the nation’s moral standing in the world.

The ADF needs a positive legal framework for military-purpose clandestine and covert activities outside of declared conflict. Encouragingly, the Albanese government is reforming defence legislation in recognition of growing strategic uncertainty, coercion and grey-zone trends, new and emerging technologies, and the changed character of warfare, including legislation that avoids proscription, reduces rigidity and inflexibility, and permits effects in situations below the conflict threshold.148 This approach should obviate the ADF’s reliance upon extended NIC authorities and immunities, thereby ensuring clear delineation between military and intelligence mandates.149 While intelligence legislation is currently out-of-scope of the reform, pursuing ADF-NIC integration (as proposed in recommendations five and six of this report) warrants consideration of two key issues:

- A simple and clear legal basis to enable unified command and control of integrated ADF-NIC operations should be enacted. Within the ADF-NIC integrated operational platform, designated senior leader and key appointments should be enabled to exercise the authorities of participating agencies and capabilities within a single operational plan. This would naturally extend to ministerial authorisation aspects.150 Where multiple, separate approvals are legislatively required, then a single ministerial authorisation instrument should enable a single operational plan. This approach not only encourages decisions to be made faster and more effectively in ambiguous and uncertain conditions but also promotes explicit ministerial-level accountability and responsibility for sensitive activities. A dual approval safeguard could be enacted, similar to Defence Force Aid to the Civil Authority ‘expedited call-out’ powers.151

- ASIS functions under the Intelligence Service Act ought to be contemporised to permit full integration with ADF unpredictable and asymmetric options. ASIS is currently prevented from planning or undertaking paramilitary activities, such as UW.152 This prohibition emanates from the second Hope Royal Commission following the infamous 1983 Sheraton Hotel incident.153 However, the accelerating threats Canberra faces today are more acute than in the mid-1980s, and ASIS has organisationally and operationally matured 40 years on. Arguably, ASIS has been more decisive in addressing its Afghanistan-era failures than the ADF has post-Brereton.154 As part of 2018 amendments, the Morrison government empowered ASIS to strengthen its self-defence capabilities but affirmed there was no modern need for ASIS to conduct special operations nor have its own offensive armed capability.155 In this vein, ASIS could be empowered to fully support and enable unpredictable and asymmetric ADF activities, while preserving the offensive capability prohibition.

Outside of declared conflict, the ADF-NIC integrated operational platform must be subject to strong legislated oversight. This is essential to assure transparency and invest confidence post-Brereton. This could be through a specifically designated Assistant Inspector-General of the ADF or a military division of the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security. The next independent intelligence community review (which received 2023/2024 budget funding) could explore this question.156 Commensurate with routine ASIS and ASD briefings, updates on the ADF-NIC integrated operational platform could be given to the Opposition Leader.157 The newly announced parliamentary joint statutory defence committee, once established, could also scrutinise aspects of the platform’s classified activity, similar to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security.158

Part C: Competing overtly

Expanding options and increasing capacity to counter and respond to grey-zone aggression in declared ways

8. Establish an Australian ‘white hull’ coast guard to counter coercion and protect sovereignty at sea.

Canberra needs a coast guard to expand its overt counter-coercion proposition. Protecting and asserting sovereignty would be its main security function, driven by Beijing’s aggressive ‘civil’ maritime forces and success in the South China Sea. The China Coast Guard (CCG), People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM), and other irregular means, such as oil rigs and survey ships, remain prominent tools in active use.159 They portend grey-zone effects which could be quickly extended into the Pacific under the guise of protecting commercial fishing, future undersea mining activities, or exercising new security rights with the Solomon Islands.

Unlike its Quad partners and many others in the region, Australia does not have a dedicated coast guard force. Furthermore, functional coherence in Canberra’s civil maritime security design is absent, with roles and resources inefficiently split between the Defence, Home Affairs, and Infrastructure portfolios.160 As it stands, two decades of high-tempo border protection operations, mostly driven by short-term political anxieties on migration, have resulted in piecemeal capability approaches. This manifested in recent years through significant personnel and availability problems in the Australian Border Force (ABF) Marine Unit and an over-reliance on contracted aerial surveillance.161 Those risks were transferred to the ADF to solve, leading to cancellations of regional presence activities, and forcing the Navy to crew and operate ABF vessels.162

As it stands, two decades of high-tempo border protection operations, mostly driven by short-term political anxieties on migration, has resulted in piecemeal capability approaches.

A coast guard offers Canberra three competitive advantages. First, white hulls answer a missing middle, enabling more graduated response options below overt military thresholds.163 Illustratively, a Navy warship countering fishing trawlers or coast guard vessels is a mismatched use of force. In the information battle, Australia could easily be portrayed as the aggressor and afford the PLA a plausible veneer to escalate with more powerful force. Second, it broadens the gamut of possible cooperation with a greater number of potential like-for-like partners.164 Though navies commonly undertake civil enforcement activities at sea, they are principally a warfighting force. Southeast Asian non-military maritime capabilities have grown considerably and their political appetite is increasing for multinational coast guard patrols.165 Perhaps unsurprisingly, the United States and Japan are both increasing their regional coast guard activity to leverage these trends.166 Third, an Australian white hull force would increase the means available to generate a persistent presence in strategically important non-militarised regions, like the Pacific Islands (customarily) and Antarctica (by treaty).167 Most Pacific recipients of Australian-gifted patrol boats are police or paramilitary arms.168 Encouragingly, the Navy’s 2022 purchase of a civilian ship for Pacific engagement shows Canberra nascently understands this value.169

An Australian coast guard could be quickly and cost-efficiently generated by re-purposing the existing annual expenditure. Initial capability would merge the current RAN patrol boat and ABF Marine Unit fleets. Navy’s Arafura- and Cape-classes are constabulary vessels already, lacking any credible naval armament.170 Retrofitting missiles to these would almost certainly be cost-prohibitive relative to commissioning a new (military-off-the-shelf) corvette.171 Personnel-wise, more flexible entry and lower training standards (comparative to the Navy) would access a broader workforce base, while the Navy — already facing major recruiting and retention shortfalls — would be released to focus on high-end warfighting and growing its nuclear submarine talent pool.

Table 6. An Australian coast guard

Indicative organisational and functional design to generate quickly and cost-effectively

| Imperatives Threat: China’s aggressive maritime coercion and grey-zone tactics Diplomatic: Partners’ comfort and preference to use coast guard-type capabilities to overtly compete and challenge Operational: Non-military dimensions of Pacific islands and Antarctic regions National Interests: Economic reliance on global shipping, third largest EEZ, environmental protection over 60,000km of coastline and 8000 islands, search-and-rescue responsibility for one-tenth of the world’s surface172 |

||

Mandate

In crisis or conflict: Defence-administered, under Navy command (as a naval auxiliary force) |

Start-state merged from Maritime Border Command Navy:

Australian Maritime Safety Authority: search and rescue |

Five-year horizon Coast Guard sub-program, sustained within the National Naval Shipbuilding Program Dual crewing for every vessel First blue-water patrol ship in-service, analogous to US Coast Guard Legend-class cutter173 Ready to assume Antarctic sovereignty mission with multi-role surveillance icebreaker |

9. Develop standing ADF rapid response options, designed for crisis and shaping missions, to reinforce regional partners and demonstrate resolve in the face of grey-zone aggression.

Deterring Chinese grey-zone aggression necessitates an expanded menu of overt, rapid ADF responses, including options that signal Canberra’s resolve and reinforce regional partners during grey-zone challenges or crises. The Defence Strategic Review emphasised that a robust ADF presence — focused on Australia’s primary areas of military interest in the Northeast Indian Ocean, littoral Southeast Asia, and the Pacific — is central to a defensive denial strategy.174 Yet during competition or crisis, graduated escalation options are needed below conventional deterrent capabilities. Key missions include reinforcing partners and defending sovereignty, strategic demonstrations (access, political will, and regional cooperation), and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR).

The ADF’s current rapid response posture is piecemeal. Unlike its allied partners, the ADF does not maintain a standing formed, resourced and rehearsed crisis capability, compromising its speed and agility when crises arise. It has historically held infantry and special forces elements at short notice for some scenarios, but not other essential air, maritime and logistics capabilities.175 Realistic mission rehearsals, involving complete force packages and testing regional basing access, seldom occur. Logistics and equipment holdings are not forward positioned, and task forces are only formed ad hoc when crises arise.176 This may have been adequate for an era when the ADF could rely upon allies to shoulder the early burden, like the withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 or the evacuation from Sudan in 2023. But this is inadequate for competitive scenarios in the Indo-Pacific where Australia should be a leading responder when challenges present.

An ADF rapid response force, under Chief of Joint Operations command, with dedicated resourcing and assets, would integrate options from the below menu. Elements would be held at six-to-twelve-hours readiness. A rotational staging node in Darwin could accommodate elements when not deployed in the region, taking advantage of new basing investment.

- A navy surface combatant deployed forward to Singapore rotated every four to six months, focused on the northeast Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia. This would increase ‘on-station’ time by reducing long transits from Australia. It follows similar US Navy arrangements since 2015 and modestly reciprocates Singapore’s army and air force training presence in Australia.177

- The Pacific Support Vessel (ADV Reliant), funded for 300 days at sea per year, as an afloat staging base.

- An army grouping for security, influence, evacuation and HADR, rotated between Darwin and Townsville brigades.

- A special forces grouping for shaping, counter-terrorism, recovery and apprehension, and maritime security.

- A cyber defence team, for ‘hunt forward’ activities, to help partners defend their networks and critical infrastructure against penetration and sabotage.178

- An airlift element capable of moving a special forces squadron or infantry company-sized grouping. This could potentially use commercial passenger types, modified for combined passenger-cargo configurations, similar to C-32B and C-40C examples.179 This would achieve rapid airlift, at low cost, without isolating aircraft from the RAAF’s small C-17 and C-130 fleets.180