The original version of this article was published on 17 January 2024 in Indo-Pacific Outlook as part of a project organised by the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Center for Indo-Pacific Affairs with the support of a grant from the Japan Foundation.

Executive summary

Undersea cables underpin 95 per cent of global communications, including data and financial transactions, and this critical infrastructure is increasingly being used as a strategic asset. So-called ‘Western’ companies used to dominate the cable industry, but now Chinese-owned companies are rapidly growing their presence and market share. China’s greater access to cables and ability to exploit vulnerabilities in the network, and negatively impact developing nations, is causing concern in Australia, the United States and Japan. This has spurred these Western countries to invest in a handful of cable projects and telecommunications providers in small developing markets, such as the Pacific Islands. Building cables where there is no commercial imperative, coupled with the imposition of new security restrictions and government legislation, is causing friction between Western governments and their private sector actors. Given the increasing interactions between the public and private sectors, this policy brief examines how to improve public-private partnerships (PPPs) on undersea cables for the benefit of both parties.

These findings have implications not only for Australia, Japan and the United States, but also for other countries looking to forge smoother collaborations with their private sectors on undersea cables in the future.

Focusing specifically on Australia, the United States and Japan, this brief draws from conversations in late 2023 with industry representatives from each of these countries. The views of major technology firms, national telecommunications companies, and private businesses operating in the Pacific region are captured. Although security and commercial considerations limited the scope of the qualitative research, three areas for improvement in PPPs emerged from discussions. Firstly, align government and industry visions for the development of the global cable architecture. Secondly, coordinate government consortia and regulatory regimes to make it easier for business to operate. Thirdly, stabilise government policy over the lifespan of the cable to help ensure industry efforts are not undermined by changes in government. These findings have implications not only for Australia, Japan and the United States, but also for other countries looking to forge smoother collaborations with their private sectors on undersea cables in the future.

Introduction

As strategic competition between the United States and China intensifies, undersea communications cables are emerging as a key battleground. Undersea cables carry upwards of 95 per cent of the world’s internet traffic and are the global arteries that underpin today’s modern, digitally enabled societies.1 Undersea cable networks are ripe for strategic competition because they provide critical communications infrastructure that is vulnerable to espionage, and they are caught in the geopolitics of development assistance and industrial policy. A handful of companies dominate the submarine cable building industry — the United States’ SubCom, Japan’s NEC Corp, France-based Alcatel Submarine Networks, and China’s HMN Tech.2 Where so-called ‘Western’ companies used to dominate the industry, Chinese companies are rapidly growing their presence.

Since entering the industry in 2007, Chinese cable building firms have quickly become one of the industry’s major players, causing concern in Australia and partner countries. In the last two decades, Chinese companies such as HMN Tech have built or repaired a quarter of the world’s cables.3 In 2019, China’s share of the global undersea cable network was 11.4 per cent and it intends to grow this to 20 per cent by 2030.4 Alongside this explosive growth, China’s national security law affords Beijing the power to compel Chinese-based cable companies to provide access to network data. This provides the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) scope to conduct cyber warfare, espionage, and intellectual property theft.5 Cable espionage is not specific to China; the United States and other Western nations have regularly engaged in such conduct since the 1970s. As it is not technically illegal to tap cables in the high seas or a coastal state’s own waters, cable espionage exists “both within and outside of international norms.”6

Figure 1. Share of undersea cables supplied by country

% of undersea cables provided by companies in a country

With both China and the United States — as well as other cable providers — having the capacity to interfere with cables, cable security often comes down to individual countries’ threat perceptions and judgements about to which state actor they would rather be vulnerable. Some country leaders have made their concerns specifically regarding China’s influence and access well known. In 2023, the outgoing president of the Federated States of Micronesia, David Panuelo, said that China wants “…control of our fiber optic cables and other telecommunications infrastructure, which would allow them to read our emails and listen to our phone calls.”7 Telecommunications experts argue that developing nations are particularly vulnerable to cable espionage by China because the Chinese government subsidises IT companies (such as HMN Tech) which enables them to bid lower prices, coercing developing countries into accepting insecure networks. This can expose countries to cable manipulation as a means of control in times of political disagreement.8

Recognising the growing significance of undersea cables to the security of individual nations and the broader region, the Australian government — sometimes independently and sometimes in partnership with the United States and Japan — has recently invested in a handful of cable projects and telecommunications providers in its immediate region of the South Pacific.

The rising security concerns associated with cables and increased interest from Western governments in PPPs are creating friction between governments and their private sectors.

From the US, Japanese and Australian perspective, investing in undersea cables and telecommunications infrastructure in the Pacific Islands serves multiple purposes at once. As well as providing developing countries with greater digital capacity and enhanced opportunity for economic growth, strategically, it crowds out Chinese-owned cables, reducing Beijing’s espionage capability. Building cables and landing stations in the Pacific Islands is often not commercially viable given its small population (2.3 million) and expansive geography.9 Because private operators lack the business case to establish dedicated cables and landing stations in the Pacific, Western governments must strike public-private partnerships (PPPs) to achieve their objectives.

The rising security concerns associated with cables and increased interest from Western governments in PPPs are creating friction between governments and their private sectors. Australia, the United States, Japan and others are imposing new security requirements and legislation on industry. As an example of the increased security requirements, in 2020 the US Government established the Clean Network program which, in effect, bans new cables from directly connecting China with the US mainland.10 The cable game is also changing with the scale and type of private companies controlling the industry. Where in previous decades most cables were owned and operated by national telecommunications companies, now major global technology companies are increasingly building new cables and buying up most capacity on this infrastructure.11 The so-called ‘hyperscalers’ Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon are purchasing approximately 66 per cent of available capacity. The dominance of these ‘Big Tech’ firms in the cable industry is only expected to grow.

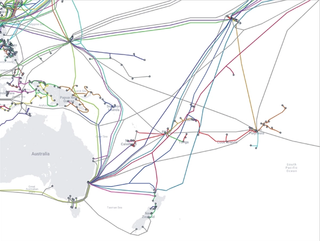

Figure 2. Map of undersea cables in the Western Pacific

With Western governments and the private sector partnering more frequently on cables, enhancing their cooperation for mutual benefit is the focus of this brief. This brief examines the recent uptick in Western government efforts to supply Pacific Island nations with undersea cables, specifically focusing on efforts by Australia, the United States, and Japan. Drawing from conversations in late 2023 with industry representatives from the hyperscalers, national telecommunications companies and Pacific region operators, it outlines private sector views on how to improve PPPs on cables going forward. Its findings have implications not only for Australia, Japan, and the United States but also for other countries looking to forge smoother collaborations with the private sector on undersea cables in the future.

Western governments’ approaches to undersea cable investment seen as ‘ad hoc’ by the private sector

Within the Indo-Pacific, the United States, Japan, and China — and to a lesser extent Australia — have provided new undersea cables and digital connectivity to small island nations for whom cable connectivity is not commercially viable, or who are vulnerable due to a lack of redundancy (i.e., an island may have only one cable connection, which, if broken, restricts communication to the entire island). Multiple reasons motivate developed countries to invest in new cables. The governments of the United States, Japan and China are naturally pre-disposed to take an interest in this industry given their countries are home to three of the four largest undersea cable firms globally — SubCom, NEC Corporation, and HMN Tech respectively. These companies design, manufacture, deploy, maintain, and operate cables, although many other industry players exist. While Australia boasts no national cable company, its government has a vested interest in increasing the security and prosperity, and hence reliability and security of communications of its neighbouring countries.

Since the mid-2010s, Canberra has been ‘stepping up’ its engagement in the Pacific — a region it sees as “deeply entwined” in Australia’s future.12 Because of their proximity to the Australian continent and the vast ocean territories they administer, Canberra sees Pacific nations’ security as fundamental to its national interests. Pacific Island nations are highly vulnerable to communications disruptions due to natural disasters, proximity to shipping, boating and fishing, and the few alternative communications lines available to them.13 Internet penetration within Pacific Island communities is among the lowest of any region in the world.14 Given the link between digital connectivity and economic prosperity, the natural and human risks to cable infrastructure, and concerns around greater Chinese influence and access, Australia is determined to be the partner of choice for Pacific nations on communications infrastructure.

Australia is determined to be the partner of choice for Pacific nations on communications infrastructure.

In recent years, Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) has embarked on several cable projects to better connect Pacific Island countries. Beginning in 2018, DFAT invested A$200 million to fund the Coral Sea Cable System, connecting the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea with the Australian mainland.15 As of 2023, this is the most expensive cable project Australia has financed to date. Canberra had not originally planned to fund the Coral Sea Cable. Australia’s involvement was triggered in 2018 by its concerns over the cable initially being delivered by a subsidiary of Chinese firm Huawei with the landing station located in Sydney, and the potential for Beijing to plug into Australia’s telecommunications backbone.16 The Australian Government had banned Huawei that same year from bidding to supply Australia’s 5G network, citing national security concerns.17

Perhaps recognising the growing reach of Chinese telecommunications companies and Beijing’s expanding influence through its Belt and Road Initiative, shortly after taking over the Coral Sea Cable project in 2018, DFAT announced a new Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific (AIFFP).18 The AIFFP is operated by DFAT, sitting within this agency’s Office of the Pacific. In 2022-23, the AIFFP’s budget was increased from A$2 billion to A$4 billion,19 comprised of A$3 billion in loans and A$1 billion in grant funds drawn from Australia’s existing aid allocation.20 The Facility has made multiple investments across the Pacific ranging from energy, water, transport, and telecommunications.21

Since its establishment in 2019, the AIFFP has committed to supporting three cables in the Pacific: 1) providing technical advice on the Timor-Leste South Cable; 2) delivering the Palau Submarine Cable; and 3) the East Micronesia Cable.22 Australia is building the Palau spur cable in partnership with the United States and Japan as the first initiative under their Trilateral Infrastructure Partnership.23 A second undersea cable project under the Trilateral Infrastructure Partnership — facilitated by the AIFFP — is the East Micronesia Cable. Announced in June 2023, the East Micronesia Cable will connect the Federated State of Micronesia, Kiribati, and Nauru.24

In addition to Australia-Japan-US trilateral efforts, the three nations have also partnered with India via the Quad to increase Indo-Pacific regional connectivity. In May 2023, the Quad launched its Partnership for Cable Connectivity and Resilience with the intention to “bring together public and private sector actors to address gaps in the infrastructure and coordinate on future builds.”25 Although Quad countries have not committed to building new cables, they plan to provide technical assistance and capacity building to developing countries, which should lead to improvements in regional communication.

The most recent announcement on cable projects in the Pacific came in October 2023 when Australia and the United States announced the Hawaiki Nui cable and the South Pacific Connect cable initiative.26 Worth A$103 million, the project involves two new cables and a new interlink cable (which connects cables together) with the potential to connect nine Pacific Island countries including Papua New Guinea, Timor-Leste, and Solomon Islands.27

Table 1. Cable projects announced by the Australian government (2018–2023)

| Year announced | Cable project and recipient nations | Sponsor countries | Industry partner(s) | Sponsor countries’ contribution to the project | Status |

2018 |

Coral Sea Cable Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea |

Australia |

Vocus Group and Alcatel Submarine Networks |

A$200 million |

Completed |

2019 |

Timor-Leste South Cable Timor-Leste |

Australia (advisory support to cable) |

Vocus Group |

A$7.2 million |

Ongoing |

2019 |

Palau Cable Palau |

Australia, Japan, United States |

Belau Corporation |

A$15.5 million |

Ongoing |

2023 |

East Micronesia Cable Federated State of Micronesia, Kiribati and Nauru |

Australia, Japan, United States |

NEC Corporation |

A$135 million |

Announced |

2023 |

Hawaiki Nui branching cables and South Pacific Connect Potential to connect nine different Pacific Island countries |

Australia, United States |

Google, Vocus, APTelecom, Hawaiki Nui |

A$103 million |

Announced |

Considering the growing involvement of the Australian, US and Japanese governments in cable projects in the Pacific over recent years, coupled with the long-term nature of delivering this infrastructure, the public and private sectors are embarking on deeper and expanded cooperation in the coming years. Heightened security concerns and pressing development needs are compelling governments and private industry to work together more frequently to deliver cables to the region, but their priorities and views are often misaligned. Improving the interactions between governments and the private sector is in the interests of both parties. To this end, the following section outlines some industry perspectives about working with the Australian, Japanese, and US governments and suggests ways companies are seeking to improve PPPs in the future.

Industry recommends public-private partnerships could improve in three main areas

Due to strategic, security, and commercial sensitivities, cable and telecommunications companies are understandably hesitant to offer candid views regarding where their engagement with government could improve. However, drawing on interviews with industry stakeholders who have been willing to discuss PPPs, this policy brief identifies three areas for improvement:

- Align government and industry visions regarding the development of the global cable architecture, security and supply

- Better coordinate government consortia and regulatory regimes to make it easier for business to operate

- Stabilise government policy over the lifespan of the cable to help ensure industry efforts will not be undermined by changes in government.

These areas for improvement relate not only to the efforts of the Australian, Japanese, and US governments but also have broader relevance for other countries attempting to navigate new PPPs on undersea cable networks.

Problem: Aligning public and private approaches to cable architecture, security,

and supply.

Solution: Increase knowledge of the topic and challenge, define a strategic vision, and move beyond the ad hoc

Government officials are driven by the national interest, paying attention to strategic, security, diplomatic and development objectives. The private sector, on the other hand, is understandably motivated by commercial and other business imperatives. Therefore, it is unsurprising that each brings different interests to their partnerships. In particular, public and private actors commonly take a different perspective on how to structure the undersea cable architecture, how to “de-risk” communication and data flows, and the amount of adequate connection supply required for redundancy.

Firstly, some in industry argue that efforts by Australian and partner governments have prioritised strategic signalling over a genuine, concerted effort to improve regional communication access and availability. They are concerned by what they perceive as ad hoc cable announcements and delivery by governments rather than a more structured investment approach. Some industry representatives perceive the Australian government as making only small investment contributions that augment the existing communications infrastructure without changing the overall balance of the architecture.28

An example cited relates to Australia’s acquisition of telecommunications company Digicel Pacific in 2021. Digicel is the largest telecommunications operator in several Pacific Island nations and Australia decided to purchase Digicel to crowd out a possible Chinese take-over.29 Media reports suggest Chinese firms such as China Mobile, ZTE, Huawei or China Telecom may have been interested in acquiring Digicel.30 The cost for Australia to acquire Digicel Pacific was A$2 billion — Australia’s largest-ever single foreign policy investment.31 After the deal was concluded, the United States and Japan offered A$77 million each in credit guarantees in the event the Australian industry partner, Telstra, defaulted.32 However, due to the low likelihood of default by Telstra, some in industry saw the US and Japanese credit guarantee offer as hollow and one that prioritised virtue signalling over substance.33

Given the large expense of acquiring a stand-alone phone company operating in the Pacific (which did not block Chinese-linked companies from operating in the region), some Pacific cable experts contend that the investment did not impact the overarching telecommunications landscape enough to be justified.34 Although Digicel Pacific does command a large market share, Chinese companies like China Mobile, ZTE and Huawei can continue to operate, with the associated risks of espionage, interference and coercion. That said, a noteworthy development is that Digicel Pacific has announced its intention to replace its Chinese-owned Huawei networks with Finnish-owned Nokia infrastructure — meaning a further reduction in Chinese access to Pacific infrastructure.35 Plus, Telstra’s shareholders and beneficiaries, including the Australian government, also stand to benefit from Digicel Pacific’s revenue, which is reported at A$719 million in the 2022/23 FY.36 So, while outside experts and observers question the cost of the Digicel deal, officials could see Australia’s investment as justified.

Industry would welcome Australia and partner countries developing a substantive “big picture” strategy regarding their approach to regional connectivity.

Setting aside both the shortcomings and benefits of the deal, overall industry would welcome Australia and partner countries developing a substantive “big picture” strategy regarding their approach to regional connectivity. In practical terms, this means considering the Pacific region as a whole, plotting out where new cables make sense for strategic and economic reasons, allocating adequate budget to support that vision, and executing the plan — alongside industry — over decades, rather than new announcements of previously unknown projects. It is unclear whether there is another example of a Western country taking this approach and working with industry in this structured manner, possibly because election cycles complicate long-term regional infrastructure planning.

Secondly, government and industry can differ in their threat perceptions and responses to securing the cable network.37 In terms of addressing the risk posed by the CCP accessing data on Chinese-operated cables, some within private industry lack confidence in the mitigation efforts of the Japanese, US and Australian governments in blocking any commercial engagement with Chinese telecommunications operators and cable system owners.

Take Japan, for example. Japan does not allow Chinese-built cables to land on its territory and, although not explicitly prohibited, Japanese officials privately discourage its telecom operators and cable owners from purchasing submarine cable systems from Chinese firms like HMN Tech.38 Similarly, the US government is considering a new Undersea Cable Control Act which could inhibit US telecommunication suppliers from forming relations with Chinese providers.39 While Australia may not technically have any laws preventing Chinese cables from landing on its territory, the fact that Canberra delivered the Coral Sea Cable System to prevent the original Huawei-affiliated cable proposal from being deployed shows Australia is willing to use informal methods to deliver the same outcome.40

While the above examples are understandable attempts by government to de-risk their cable systems, an emerging private sector view is that the current official policies do not appreciate the commercial realities or impracticality of completely severing from Chinese telecommunications providers in the Pacific Islands. Industry members have highlighted that rejecting any and all private-sector cooperation with China can have negative consequences. One is that Chinese telecommunication and cable system owners could end up exclusively using Chinese system suppliers — like HMN Tech — without Japanese and American providers competing. This could allow Chinese system suppliers to become more dominant as a result. The private sector view is that by simply prohibiting Japanese and American companies from working with Chinese cable owners, their commercial opportunities will narrow and Chinese companies fill the void. This could potentially lead to the proliferation of more ‘untrusted’ networks.41

An obvious but integral way to address this issue is for officials and the private sector to commit to deeper and more regular dialogue. Before the Australian, US and Japanese governments engage their private sectors, however, they must seek to align their domestic administrations as a first step. A key area for discussion could be whether these governments are willing to invest resources beyond what they have already committed to taking a more dominant position in Pacific Island cables. If not, they would need to clarify what sort of Chinese presence they would allow and which they will not because that remains unclear. Once there is a combined position between the three governments, they could then better engage their private sectors.

Industry members have highlighted that rejecting any and all private-sector cooperation with China can have negative consequences.

More dedicated dialogue between the public and private sectors could allow government to make its concerns clearer and give industry — cable system owners and suppliers, and telecommunications operators — an opportunity to present its case on whether those concerns are valid and reflect commercial and technical realities. These discussions should happen domestically within the United States, Japan and Australia and their private operators before the three nations share this information between themselves. As it is likely all three countries will have various approaches, they should seek to align their domestic parties as a first step.

Thirdly, the public and private sectors lack a common understanding of what constitutes an adequate supply of cables. There are differences in perception and levels of knowledge between government officials and the private sector about the critical use cases for cables, meaning the number of ways cables can be compromised and the amount of redundancy required. Given public and private actors have separate opinions on critical supply, the two groups make different judgements about how many cables and what data transmission capacity provides enough redundancy.

A discussion forum that brings together all the relevant stakeholders is required to create a shared understanding of the critical uses of cables, how they might be compromised during a conflict, and what capacity is enough to ensure critical supply. A similar recommendation for an interdisciplinary group of government regulators, security experts, and industry leaders to convene to discuss cable security has been made in the US context.42 A key area for discussion in Australia could include the critical connectivity routes undersea cables should take.

Problem: Coordinating government consortia and regulation

Solution: Establish more regular domestic and international dialogues on regional cabling

Business also reports challenges related to a lack of coordination between different governments on cable delivery and regulation. At times, government agencies within the same country operate independently of each other, resulting in poor domestic coordination even before attempts are made to cooperate with other countries’ governments and regional recipients. This problem of lacking domestic coordination on undersea cables has been identified in the United States, including by researchers at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in 2022, who recommended the US government establish a centralised team that draws in relevant agencies and elevates digital infrastructure as a policy priority.43

When an undersea cable project is delivered in partnership with multiple governments, the coordination challenges increase. The Australia-Japan-US Trilateral Infrastructure Partnership and the Quad partnership with India provide examples.44 Each government and its respective implementing agencies have different priorities, implementation approaches, and resource capacities. One industry representative described the dynamics between Australia, the United States and Japan as “co-petition,” with the three governments both cooperating and competing, rather than working in concert.45 Again, the solution here is more dialogue to align different governments, but not until they have coordinated domestically.

In addition to better inter- and intra-government coordination, regulations need to be aligned to provide the right enabling environment for business. The regulatory environment for undersea cables is complex, involving different jurisdictional zones and maritime, cyber, critical infrastructure and telecommunications policy.46 Harmonising these separate moving parts as much as possible would support private sector efforts.

Problem: Desire for policy continuity for greater project stability

Solution: Seek bipartisan support for cable projects as early as possible

Increasing policy continuity across changes in government is a commonly held interest throughout the private sector: cable and telecommunication companies are no different. Small, medium and large firms all highlighted a major irritant in PPPs — the lack of continuity in governments’ visions and ambitions over the lifespan of a single cable project. As the number of government bodies involved in a single cable project increases, so too does the project complexity.

Changes in government can cause instability for cable and communications companies causing delays and additional expense, resulting in lower returns.

While some undersea cables connect domestically, often cables connect two or more countries, meaning at least two federal governments, in addition to local or state authorities, can be involved. As cable projects can take several years to complete, during that period there can be changes in government in recipient nations or delivery partners. Changes in government at any level can lead to project disruptions and new or changed requirements. For example, during the 18-month delivery of the Coral Sea Cable between 2018 and 2019, there was a change of government in the Solomon Islands causing delays.47 Similarly with the Timor-Leste South cable, public and private stakeholders were close to finalising contracts when a new administration in Dili was elected and political instability increased.48 Changes in government can cause instability for cable and communications companies causing delays and additional expense, resulting in lower returns.

The private sector is understandably eager to reduce the instability caused by changes in government wherever possible. To support this outcome, continuity of ambition across successive governments is key. Prior to embarking on new cable projects, participant governments should be mindful that cable lifespans outlive individual government terms — and plan for disruptions. In democratic systems changes in government can and do happen frequently, meaning it is unlikely current serving governments can do much to create more stability for business. However, securing bipartisan support for cable projects, contingency funding and a robust business case can help provide some degree of stability for business.

Looking to the future of public-private partnerships

Given the increasing strategic competition engulfing cables and the critical need for digital connectivity within emerging economies, development and control of undersea cables will continue to preoccupy Australia and partner countries for decades. To achieve their national objectives, governments will need to maximise their engagement with private operators. To improve on the current track record for future projects, Western governments should note industry’s concerns and take steps to improve their approach. Members of the private sector have communicated that projects are sometimes negatively impacted by governments’ lack of a strategic vision for the cable architecture, poor government coordination and lacking policy continuity.

The development of a shared vision for action, additional frameworks for communication, and greater attention to inter- and intra-government coordination would benefit both sides and, ultimately, the recipients of these cable projects.

To support better outcomes, the development of a shared vision for action, additional frameworks for communication, and greater attention to inter- and intra-government coordination would benefit both sides and, ultimately, the recipients of these cable projects. As the appetite for digital connectivity in developing nations grows and strategic competition intensifies, the Australian, Japanese and US governments must foster closer and more trusted partnerships with the private sector, starting with the areas outlined in this brief.