Executive summary

- The United States’ Indo-Pacific presence, particularly its naval forces, represents one of the most visible and significant indications of US commitment to the region. However, the US Navy’s ship count is shrinking and its Indo-Pacific presence relies on a small number of concentrated bases and operating locations, many of which lie within range of China’s growing array of long-range strike weapons and counter-intervention capabilities. Crucially, this currently includes many of the Navy’s in-region logistics, maintenance, and sustainment capabilities, assets likely to be high on the list of initial People’s Liberation Army (PLA) targets in the event of a conflict.

- Fortunately, there are ample opportunities for the US-Australia alliance to offset these vulnerabilities. Australia’s significant domestic maritime capacity, ranging from shipbuilding to repair and maintenance, offers viable options to reinforce and underwrite US maritime presence in the region. Its strategic location also lends itself to combined basing arrangements that would enhance alliance posture.

- To help ensure the ongoing engagement of US power in the region and to underwrite effective collective deterrence efforts, the so-called “five R’s” of logistics — refuel, rearm, resupply, repair and revive — should be prioritised by alliance managers. Specifically, policymakers should focus on building out the Combined Logistics Sustainment and Maintenance Enterprise (CoLSME) announced at AUSMIN 2021.

- Australia should take a leading role encouraging, facilitating and pursuing a combined approach to naval fleet support in five high-priority areas: shipbuilding and key warfighting enablers; basing and infrastructure; sustainment; prepositioning; and maintenance. These are essential inputs to a strategy of collective defence aimed at shoring up a favourable regional balance of power.

Australia should take a leading role encouraging, facilitating and pursuing a combined approach to naval fleet support in five high-priority areas: shipbuilding and key warfighting enablers; basing and infrastructure; sustainment; prepositioning; and maintenance.

Recommendations

This report lays out a case and provides a menu of policy options for how Australia can lead efforts to support an enduring and resilient US maritime posture within the alliance.

On shipbuilding and addressing alliance capability shortfalls, Australia could:

- Initiate a joint study of US and Australian naval supply chains and identify potential areas for either co-production of critical equipment or supply chain opportunities for Australian shipbuilding.

- Invest more in mine countermeasures, particularly in a crewed vessel to replace the retiring Huon-class minesweepers.

- Explore the development of either an indigenous or shared design for a submarine tender capable of supporting Australia’s current submarine force and future nuclear-propelled AUKUS-class boats and allied platforms.

On basing and infrastructure, Australia could:

- Initiate development of an integrated/combined headquarters in Northern Australia.

- Develop a roadmap toward permanent basing structures for US forces in Northern and Western Australia. This should be accompanied by policy shifts aimed at lengthening rotations or shifting to a permanent basing structure with US and Australian forces co-located.

- Invest in the Gascoyne Gateway development and incorporate it into Australian defence planning as well as alliance operations.

On sustainment, Australia could:

- Ensure that the US Navy (USN) and Royal Australian Navy (RAN) maintain and exercise the ability to share fuel and food stores and formally commit to doing so at the operational level of command, with a defined periodicity and short notice to participants.

- Exchange liaisons with the USN in support of combined logistics. This could take the form of liaison officers ashore, or even exchange officers working as staff augmentees within the respective logistics departments of operational staffs.

- Integrate combined logistics forces by conducting crew exchanges between logistics ships and embarking allied helicopters and flight crews to conduct vertical replenishment operations.

- Create a linkage between the US Maritime Security Program (MSP) and Australia’s Strategic Maritime Fleet to share best practices and lessons learned as Australia’s Strategic Fleet Taskforce develops the concepts and policies that will govern Australia’s capability.

On prepositioning, Australia could:

- Offer pier space in Australia for US Maritime Prepositioning Ship Squadron (MPSRON) ships. Doing so will offer benefits to the alliance both in peacetime and contingency, bringing critical materiel deeper into the region from existing bases in Diego Garcia and Guam.

- Within CoLSME, explore transitioning afloat prepositioned stocks from MPSRON ships that may be unfit for service or decommissioned into ashore facilities in or around Darwin and Fremantle. Explore forward rotations and/or basing of smaller sealift platforms and maritime logistics capabilities.

- Within the scope of Australia’s Guided Weapons and Explosive Ordinance (GWEO) ensure initial execution and sustained investment in the production, maintenance, and stockpiling of key naval munitions in Australia, with emphasis on strike weapons such as SM-6, Tomahawk, and Mk 48 torpedo.

On maintenance, Australia could:

- Advance planning for a Henderson drydock. Doing so would not only address a critical maintenance need but would also underwrite the Australian Government’s commitment to the 2023 Australian Defence Strategic Review and the operational side of AUKUS.

- Build a combined maintenance plan for combatants and auxiliaries which maximises pier and personnel availability in Australia and secures a reliable schedule of work to allow defence contractors and suppliers to plan and hire with confidence.

- Request and complete transfer of US floating drydock technology to Australian industry, which would be vital for supporting eventual SRF-West forces in Western Australia.

Introduction

Since the conclusion of the Second World War, forward deployed US naval power has represented one of the most explicit, visible signals of US commitment to Asia. It would not be hyperbolic to say that the US naval presence has underwritten both the regional security architecture as well as the economic order that has lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty. Today, both this order and the corresponding US Navy (USN) forward presence are being challenged by Beijing at a scale that dwarfs even that seen during the height of the Cold War. Simultaneously, the United States is struggling to maintain even the present size and condition of its ageing fleet, while also struggling to grow capability or change its operational practices and culture or respond to new threats. Critically, the United States lacks sufficient domestic shipbuilding, global sustainment and maintenance, and overseas basing to balance Beijing’s naval power on its own and must find new ways to work with regional allies to meet shortfalls and maintain a favourable balance of power.

Such challenges create significant opportunities within the US-Australia alliance, especially in the wake of the announcements of the AUKUS partnership and the 2023 Australian Defence Strategic Review. In some respects, the alliance has remained less developed than others the United States maintains in the region, such as the US-Japan relationship, which provides for combined basing and repair throughout the Japanese home islands with US forces and Japan Self-Defense Force personnel sharing key facilities in common. The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) and the US Navy commonly support one another with at-sea logistics, expanding their operational capabilities while effectively husbanding scarce logistics assets. Though the US-Australia alliance has moved in this direction in the last decade with initiatives such as Marine Rotational Force — Darwin (MRF-D), Australia and the United States could do significantly more in a combined format to enhance the alliance’s posture by pursuing more opportunities to demonstrate interoperability and interchangeability in both operations at sea and logistics and basing ashore.

To this end, the “five R’s” of logistics — refuel, rearm, resupply, repair and revive — should be immediate priorities for allied exploration and investment.1 Despite the advanced capabilities fielded by both partners in the alliance, as well as the considerable shared history of combined operations, many of these capability areas remain underdeveloped both within the respective navies as well as within the alliance context. In the United States, for instance, critical capabilities such as reloading ships’ vertical launch systems (VLS) at sea have been entirely lost following the Cold War because such expeditionary capabilities were not required of a force enjoying global dominance.2 Since the conclusion of the Cold War, US public shipyards and drydocks have been sold off and maritime workforces have been allowed to wane.3 US naval forces have also been steadily reduced, declining from a height of almost 600 ships in 1990 to a battle force of under 300 in 2023.4 Simultaneously, forward naval presence has shrunk from its Cold War peak, now limited almost exclusively to a chain of large bases in Japan. The United States also maintains a degree of rotational access in Singapore, but its toehold in the small city-state is hardly comparable to its former base in Subic Bay which was nearly the size of Singapore itself.

The United States lacks sufficient domestic shipbuilding, global sustainment and maintenance, and overseas basing to balance Beijing’s naval power on its own and must find new ways to work with regional allies to meet shortfalls and maintain a favourable balance of power.

In contrast, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has only increased its investment in these key sectors over the past 20 years. Seven of the world’s top 10 container ports are now in the PRC and China is the world’s second-largest shipbuilding nation. The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is on a path to reach 400 ships by 2025, having already surpassed the US Navy in number of hulls before 2023.5 And the PLAN is largely still a regional force that conducts occasional deployments outside the Indo-Pacific. The US Navy is a globally dispersed force, with ships, submarines, and aircraft deployed around the world. Comparisons with the PLAN become more ominous when considering that immediately available US naval forces in the Indo-Pacific, those which belong to the US Pacific Fleet, number approximately 200 and are spread from Japan to the west coast of the continental United States.6 Its counter-intervention weapons, central to its strategy of anti-access/area denial, include an extensive suite of munitions ranging from manoeuvrable ballistic missiles to advanced anti-ship cruise missiles. These weapons give the PRC options for attacking all US force concentrations west of Hawaii with relative ease, including large combatants at sea. Though not an infallible or undefeatable weapon, they do pose a significant challenge to the US security presence in the Indo-Pacific, both with regard to ships at sea and bases ashore.

Addressing alliance capability shortfalls with Australian shipbuilding

The United States no longer has the shipbuilding capacity to grow its fleet at even its current target for expansion. Current levels of investment are the highest in the world and yet, when combined with decrepit shipbuilding and troubled designs, are insufficient to meet declared US shipbuilding targets.7 The largest problem currently facing the US shipbuilding industry is that it has developed into a monopsony, where there are many sellers and providers but only one buyer — the US Government. As the sole customer, the government’s fluctuating shipbuilding budgets and changing strategy do not provide sufficient or stable investment that would allow shipbuilders to hire and retain skilled workers.8 The US Navy issues a new shipbuilding plan yearly, which is logical in the context of US Government budget cycles but does not align with industry needs, which must plan longer term to ensure their own commercial viability and preserve shareholder value. Sustained investment in training and retaining a skilled US maritime workforce is thus constrained by the inconsistent demands of the US Government, while the government’s plans are constrained by the workforce available. This creates a vicious cycle that manifests itself in under-delivery on intended shipbuilding timelines.9

Australia’s own shipbuilding capabilities are significant and would be valuable in generating capacity for growing the US fleet. However, US domestic politics are almost certainly too fraught for that to come to fruition, with enacted legislation in the US forcing shipbuilding to “Buy American.” The 2022 defence budget mandated certain parts and systems aboard US ships that could not be funded unless produced domestically, ranging from steering controls and pumps to cranes and propellers.10 New, yet-to-be-passed legislation in 2023 has targeted a requirement for percentages of the components for US ships to be built domestically, rising steadily on a pre-established trajectory set to hit 100 per cent by 2033.11 There is, however, a caveat for expanding sourcing to members of the National Technical Industrial Base (NTIB) — the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and Canada — if domestic production is cost-prohibitive or the items are not available in the United States.12

Given this constraint, Australian shipbuilding strengths might be best leveraged within the alliance by honing in on key capability areas where the United States has limited strength and is unlikely to recover without significant changes to its domestic shipbuilding situation. Certain warfare areas offer important opportunities for the RAN to step in, as well as opportunities for domestic investment in Australian shipbuilding. The first of these is in mine countermeasures (MCM). China, Russia, North Korea, and Iran are all enthusiastic employers of sea mines and have vast inventories of the same. The PRC in particular retains considerable ability to deploy large amounts of mines in a short period by leveraging its navy as well as its maritime militia, which has reportedly received mine warfare training in the past.13 However, the modern US Navy possesses a very limited MCM capability, with eight ageing minesweepers that are all scheduled for decommissioning before 2030 and no replacement identified. Its uncrewed capabilities in the MCM arena are still developing. In Europe, this shortfall is balanced by a number of NATO navies that continue to invest robustly in the MCM mission and keep a viable capability alive within their own navies, as well as contribute to Standing NATO Mine Countermeasures Groups (SNMCGs).14 Australia, along with Japan — which operates its own Mine Warfare Force — might support US Navy regional presence by taking the lead in this warfighting area. While Australia’s last four traditional Huon-class MCM vessels are approaching the end of their service lives, the RAN is exploring multiple concepts for uncrewed underwater vehicles and support craft to fill the capability gap that will follow.15 But uncrewed MCM technologies are still maturing, and their ability to completely replace traditional crewed MCM ships is questionable.16

Filling the gap left by the retirement of the RAN’s MCM ships, as well as the approaching obsolescence of the US MCM fleet, would require building or acquiring a workable crewed MCM ship as well as continuing to develop the RAN’s uncrewed capabilities. A Luerssen OPV-80 variant, currently planned for two hulls, designed to replace the RAN’s four remaining Huon-class MCM ships would be a useful contribution but without significantly increased investment would not even replace the RAN’s lost capacity, let alone that of the US Navy’s remaining eight MCM ships, the last of which are slated for retirement by 2027.17 The Arafura-based MCM also has yet to materialise and is unlikely to do so before the Huon-class leave service.18 Alternatively, Japan’s new Awaji-class minesweeper offers a modern design for a dedicated MCM ship at roughly A$183 million per ship, even less than the per hull cost of the Arafura-class.19 Exploring the possibility of acquiring finished ships or transferring technology to build an Australian variant of the Awaji-class should be possible within the existing transfer of defence equipment and technology agreement between Australia and Japan.20 The Huon-class was itself a derivative of an Italian design, the Gaeta-class, which allowed it to be designed and built faster due to the reduced workload in the concept and design phase — leveraging similar efficiencies might be an optimal path for a robust Australian MCM force.21

Australian shipbuilding strengths might be best leveraged within the alliance by honing in on key capability areas where the United States has limited strength and is unlikely to recover without significant changes to its domestic shipbuilding situation.

As the RAN prepares to host nuclear submarines from the United States and United Kingdom, as well as sending combined crews to sea, submarine supply is another area where Australia might take the lead in supporting operations. Whereas the United States operates one of the largest submarine forces on earth, it operates only two submarine tenders — both of which are woefully dated. The US Navy decommissioned all but two of its L.Y. Spear-class submarine tenders at the end of the Cold War. The two remaining vessels, USS Emory S. Land and USS Frank Cable, were launched in the 1970s and are both homeported in Guam.22 Without similar ships, US submarines would be hard-pressed to find support ashore in a wartime contingency, with Japanese ports under constant threat of ballistic missile attack. Without access elsewhere, US submarines would be forced to travel back and forth from the Western Pacific to Guam for support requirements like food and weapons. Should Australia elect to develop an at-sea submarine tender capability it might be well received for supporting the SRF-West organisation as well as other deployers in the region, negating the need for nuclear-powered submarines to enter port for services and resupply of stores. In contingency operations, these tenders could also support expeditionary reloading of munitions away from easily observable port facilities. Such a vessel could start making an impact for the RAN well before delivery of the planned Virginia or AUKUS-class boats, a modernised tender could add considerable resilience and extended range to the Collins-class before their eventual replacement.

Recommendations

- Conduct a joint study of US and Australian naval supply chains and identify potential areas for either co-production of critical equipment for shipbuilding, or potential supply chain opportunities for Australian industry to take a more meaningful role in US Navy shipbuilding.

- Mine countermeasures and mine warfare are another area where the RAN maintains significant expertise and, conversely, the United States is relatively weak. Approaching the MCM issues from a combined warfighting perspective would be more effective, as the United States is unlikely to significantly elevate its own investment in this key area and the RAN is making strides toward a modern force of support craft and autonomous MCM tools.23 Investing more seriously in an MCM replacement, whether that takes the form of a Luerssen design, transferring technology to build an Australian variant of the Awaji-class, or purchasing hulls directly, would be a critical addition to the alliance as well as add considerable capability to the US-Australia-Japan Trilateral Security Dialogue.

- Invest in key maritime enabling areas. This could take the form of developing an indigenously designed submarine tender or transferring technology to modernise a legacy US tender design for modern operations. As the US Navy takes the initial steps toward identifying the design for its next-generation sub tender, AS(X), there might be the opportunity for inter-alliance collaboration on that design with an eye toward developing a vessel that both countries could build domestically.24

Basing and infrastructure

The US Navy’s footprint in the Indo-Pacific has remained largely stagnant since the withdrawal of US forces from the Philippines in 1991. After shifting a small number of personnel to Singapore, the majority of changes saw access become more limited and existing bases expand. The period of the Global War on Terror, beginning in 2001, saw US attention focused outside the Indo-Pacific with priority on the Middle East and Southwest Asia. The US operational naval presence in the region was effectively reduced to heavy concentration across Japan’s islands with no other meaningful operational forces inside the second island chain. Hawaii and the US territory of Guam made up the balance of the US Pacific Fleet’s presence. The strategic reawakening that began during the Obama administration, which took the form of the ‘Pivot to Asia’ or ‘Pacific Rebalance’ sought to address the growing disparity in military force by bringing more US forces into the region, but without new access arrangements, those forces were simply added to already-vulnerable sites in places like Japan.25

The US push to expand its access came too late. By the early 2000s, Chinese military and economic power, along with their accompanying regional influence, were too significant in regions like Southeast Asia for those states to even consider hosting US forces in a meaningful way due to the likelihood of countervailing pressure from Beijing. In recent years, as US competition with China intensified, the idea of hosting US forces has become even less palatable as states aim to hedge and balance their way to a middle position between the competing superpowers.

In recent years, as US competition with China intensified, the idea of hosting US forces has become even less palatable as states aim to hedge and balance their way to a middle position between the competing superpowers.

The only meaningful exception to this in Southeast Asia is Singapore, which plays host to several American military commands including Commander, Logistics Western Pacific (COMLOGWESTPAC) and Military Sealift Command Far East (MSC-FE). The United States and Singapore have also agreed on a regular presence for US ships on rotational deployments to the island nation, as well as routinely hosting US nuclear-powered aircraft carriers and nuclear submarines, as well as other combatants. However, even this access might be questioned in the event of a contingency that saw the United States facing off against the PRC.26

The dilemma facing the United States is a paucity of access in its most consequential area of operations, combined with the fact that its existing access is well within the range of a suite of weapons designed by its primary adversary to target those facilities and its forward-deployed forces. Even in a peacetime contingency, this concentration of military basing in Northeast Asia will lengthen response times to emergencies like natural disasters or other humanitarian crises. Dispersing US forces will not only lessen the likelihood of a surprise attack catching a majority of the US Seventh Fleet in one place but also amplify US ability to project naval power in peacetime to respond to regional needs.

Contemporary discussions of increasing visits or rotations of US naval forces, particularly surface ships, at HMAS Stirling predate the AUSMIN Consultations of 2012, which were held in Perth, and the Obama-era pivot. In March of 2012, an ADF Posture Review identified the base as a location that “could support an enhanced US naval force posture in the Indian Ocean” and highlighted past instances of US destroyers using Fremantle as a location for rotating ships’ crews.27 While in Western Australia for AUSMIN 2012 then-Secretaries of State and Defense, Hillary Clinton and Leon Panetta, toured the base with their counterparts Foreign Minister Robert Carr and Defence Minister Stephen Smith. Shortly thereafter, the idea of basing a US Carrier Strike Group in Western Australia was suggested in a report from the US Center for Strategic and International Studies and flatly rejected by the Gillard government. Comments from the Australian Government later in 2012 indicated an expectation that US ship visits at HMAS Stirling would increase, but that expectation remained largely unfulfilled until the advent of AUKUS, which contained significant commitments for increased US presence in Australia.28

The Submarine Rotational Forces West organisation (SRF-West), announced in March 2023, offers an advanced model for realising this decade-old commitment in the form of future US surface presence as well as planned submarine deployments.29 Not only does the arrangement put forward in the AUKUS architecture bring persistent US forces forward into an area of the Indo-Pacific less commonly trafficked, but also creates new effects on the regional deterrent balance by introducing combined crewing of US warships. While this integrated crewing scheme will first and foremost provide needed RAN sailors with training on the operation of nuclear-powered fast attack submarines, it also complicates the targeting of those submarines by US adversaries.

The infrastructure investment to build and host those submarines will be considerable. When accounting for the shipbuilding and other associated elements of the AUKUS Pillar I agreement, some estimate the initiative will create approximately 20,000 jobs for the whole of Australia over the 30-year life of the AUKUS submarine program. Nuclear-powered vessels require specialised equipment and operators, and existing basing at HMAS Stirling will necessarily be expanded to host US and UK nuclear submarines before Australia’s own boats are delivered, necessitating 500 direct jobs to be created in Western Australia between 2027 and 2032 to sustain that force. Additional warehouses, wharf upgrades, and sustainment facilities for HMAS Stirling are also accounted for within the Albanese government’s strategy.30 Adelaide, the intended home of Australia’s Submarine Construction Yard, will also see considerable economic benefit from the initiative, with up to A$2 billion earmarked for investment into building and upgrading facilities as well as upskilling and training the Australian shipbuilding workforce.31 South Australia is expected to add nearly 4,000 new jobs in the process of developing the new submarine yard for the AUKUS-class, with projections reaching up to 5,500 additional jobs for the building of the submarines themselves.32

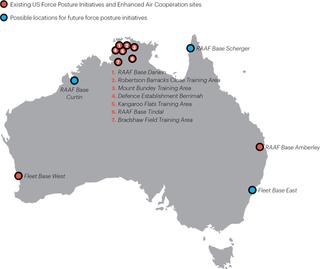

Figure 1. Current and potential allied force posture in the Indo-Pacific

Other existing bases in Australia should be considered for similar arrangements. While basing combined naval forces in HMAS Stirling is a significant step forward in alliance maritime posture, it does simplify any adversaries’ potential targeting calculus if seeking to attack those vessels in port. Expanding and regularising basing and operational access for all classes of naval vessels, as well as maritime patrol forces, would necessarily go beyond the current model of occasional ship visits. This was already identified in the 2023 AUSMIN Joint Statement as a priority for expanding maritime patrol and reconnaissance aircraft (MPRA) cooperation, with plans to rotate US aircraft through air bases in the Australian northern base network. Also included in the 2023 AUSMIN outputs was a commitment to begin introducing US army watercraft into that same region, which dovetails neatly with the 2023 Australian Defence Strategic Review’s focus on littoral manoeuvre and maritime.33

One facility that should be of particular interest to the alliance is the Gascoyne Gateway carbon-neutral deep water port project under development in Exmouth, Western Australia. The project is designed for the transfer of oil and gas, as well as break-bulk cargo, and has been designed with carbon neutrality in mind from the outset.34 The entirely civilian-funded port facility could greatly benefit the alliance’s operational capabilities in the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia, while simultaneously creating utility for the local community.35 Its potential significance for the alliance is multifaceted. Geographically, the port is Australia’s closest jumping-off point to the Sunda Strait, the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, and Diego Garcia. It is located between two Australian naval bases in Darwin (3,171km) and Rockingham (1,250km). Its strategic location, if employed as a refuelling and resupply base for ships and submarines operating from Darwin and Fremantle, could drastically extend the operational reach of those forces into Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean. Its planned 30 million litre fuel storage for diesel and aviation fuel is considerable, and room remains on site for additional storage of up to 500 million litres.36 The port’s proximity to RAAF Base Learmonth (30km) and Naval Communication Station Harold E Holt (6 km) is an advantage that would negate the need for transporting fuel in trucks overland to those locations from Perth; the project operators have validated a concept for building aboveground pipes from the port to those bases, cutting out the 1,250km transit for fuel currently required.37 Increased fuel storage would also add resilience to those operating locations, supporting extended flight operations from RAAF Base Learmonth as well as enabling operations for the communications station. The port’s distance from the city of Exmouth makes it a prime location for munitions loading as well, provided the site is equipped with the necessary supporting infrastructure which alliance investment could ensure — should that option be pursued, it could add a second location in Australia for loading submarines with Mk 48 torpedoes, currently limited only to HMAS Stirling. The port is sufficiently sized to accommodate every ship in the RAN as well as most of the USN, barring nuclear-powered aircraft carriers. The deep waters off the port itself are attractive for submarine operations, allowing resupplied boats to dive almost immediately after leaving port rather than transiting for extended periods on the surface. For the local community, the ability to directly import fuel would generate considerable savings — Exmouth residents pay approximately 20 cents more per litre for both diesel and unleaded fuel than major metropolitan areas in Australia due to the costs of extended overland transport of fuel.38 Development of the site is expected to create around 400 jobs during construction as well as 70 more full-time positions in the operational facility.39

Recommendations

- Develop an integrated/combined headquarters in Australia, located somewhere within the Northern Base Network or perhaps co-located with HMAS Stirling. This is a long-term goal that cannot be achieved overnight. For example, the US-Japan alliance, which has far more experience in combined naval operations, is only now working toward updating legacy command and control (C2) structures that are not combat-oriented.40 This is an effort that would require a significant outlay of political capital and effort to break down bureaucratic stovepipes and think creatively about operational control and employment of forces. However, the US-Australia alliance’s singular focus on a significant threat should provide some degree of attention and impetus for change. The capability areas identified in AUSMIN 2023 (MPRA and littoral manoeuvre/sealift) are two that lend themselves to combined operations particularly well.

- Develop a roadmap toward permanent basing structures for US forces in Northern and Western Australia. A successful model for rotational forces has been proven effective for more limited aims, but for higher-end warfighting concepts and combined operations, a more permanent alliance structure will be required to underwrite real interoperability. Data from polls conducted as recently as 2023 indicate that more than half of Australians are at least “somewhat supportive” of the idea of allowing US basing in Australia, and that result is consistent over at least a decade of recorded data.41

- Invest in and incorporate the Gascoyne Gateway development into Australian defence planning as well as alliance operations. This could take the form of an outright purchase by either the US or Australian governments, or a paid arrangement which secures preferential access for the Australian Defence Force (ADF) and US forces. The ADF and US forces already maintain similar arrangements, including a commercial contract which provides access to the Australian Marine Complex (AMC) floating dock at Henderson and the contractor-owned/contractor-operated (COCO) fuel facility in Darwin.42 The extended operational range and flexibility offered by the Exmouth facility would benefit the naval and air forces of both alliance partners, add resilience to the base network in Western Australia, and offer flexibility for reloading ships and submarines, as well as deliver considerable economic benefit to the immediate region.

Sustainment

The United States Navy operates the world’s most sophisticated seagoing resupply force, with a fleet of oilers and cargo vessels larger than many navies. Yet its capabilities are stretched thin by the global nature of US operations, and many argue that US sealift and supply are being pushed beyond their breaking points. A combat logistics force of 30 ships appears to be a significant number until diluted by time, speed and distance, at which point resupplying the US fleet starts to become a problematic proposal — and that reflects peacetime demand without the undue threat of loss or damage.43 In a high-end contingency against an adversary such as the PLA Navy, those already-scarce supply vessels would be immediately targeted as a critical centre of gravity for US naval operations. Some areas of at-sea resupply have been almost entirely lost in several decades of relative peace on the seas, most notably the aforementioned submarine tenders, large vessels designed to provide maintenance and logistic support at sea to nuclear submarines.

As Australia extends its gaze further from its shores and the United States is forced to examine long-held assumptions about access and resupply inside the first island chain, the two navies will more commonly sail through and rely upon the same water space, which creates more opportunities for events like the US-Japan Interchangeable Logistics Exercises.

While the United States does possess and operate the world’s largest at-sea logistics force, under the command of the US Transportation Command’s (USTRANSCOM) Military Sealift Command (MSC), its ships and its workforce are in critical states. The ships in the MSC Strategic Sealift fleet are ageing rapidly, and their material condition is cause for significant concern. The US Merchant Marine is nearly 2,000 officers short of its wartime requirements and in recent years has only been able to generate 65 per cent of its required capacity.44 The average age of its personnel is nearing 50 and still increasing, a troubling trend that indicates recruitment into the profession is lagging.45 In a profession as physically demanding as crewing and maintaining a seagoing vessel, an ageing workforce is problematic. Perhaps more critically, its strength is globally dispersed, which stretches this heavily taxed force to its limits and makes its scarce vessels a high-priority target and critical vulnerability in a wartime contingency. Integrating Australia’s at-sea logistics vessels into a combined pool of resources would further enable refuelling and resupply capabilities and also open up more opportunities for Australian combatants to do the same with US resupply ships, thereby expanding and reinforcing the operational reach of both navies. With one Supply-class Auxiliary Oiler Replenisher (AOR) based at Fleet Bases East and West, HMAS Supply (II) and HMAS Stalwart (III) respectively, the RAN’s replenishment fleet is limited in numbers but capable.46 Each ship can deliver 470 tons of provisions, carry 1,450 cubic metres of JP-5 jet fuel, 8,200 cubic metres of marine diesel fuel, 140 cubic metres of fresh water and 270 tons of ammunition, and have an operational radius of about 6,000 nautical miles.47 Additionally, in October 2022, the Australian Government committed to establishing a Maritime Strategic Fleet made up of 12 Australian flagged and crewed vessels to be available for Australia’s needs when called upon.48 This concept is similar to the US Maritime Security Program (MSP) fleet, a group of commercially viable ships held on retainer to support US combat logistics in wartime. The MSP consists of 60 ships and is capped at that number by Congress. Australia’s MSF and the US MSP should have some level of coordination to identify potential areas for cooperation and, at the very least, share lessons learned and best practices. Notably, China’s shipyards build the equivalent of the US MSP every year.49

This is not a novel concept — the United States already conducts similar logistics sharing with Japan, its other pivotal Indo-Pacific ally. Japan sent its replenishment ships into the Indian Ocean to refuel US warships in 2001 and then, after a short hiatus, sent them back again in 2008.50 Japan’s 2015 “Legislation for Peace and Security” saw the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) expand its operational integration with the United States, going beyond exercise logistics to refuelling US ballistic missile defence ships as well as escorting US logistics vessels.51 In 2016, the bilateral Acquisition and Cross Servicing Agreement (ACSA) was revised to expand the conditions under which Japan could provide munitions to American forces, and geographic restrictions on those operations.52 The JMSDF also maintains a permanent liaison officer assigned to Commander, Logistics Western Pacific (CLWP) in Singapore, the organisation responsible for US logistics operations in the Indo-Pacific.53 The presence of such a liaison has enabled the US-Japan alliance to optimise and streamline logistics arrangements, improve communications, and remove obstacles to short-notice opportunities to work together.54 These operations are conducted within the hierarchy of US Naval Supply Systems Command (NAVSUP) Fleet Logistics Center Yokosuka, the hub for all US logistics support between Guam and Diego Garcia.55 This logistics footprint has its origins in the conclusion of the Second World War and is thus unsurprisingly mature. However, the United States, at the urging of the US ambassador to Japan, is also now reportedly examining the feasibility of using Japan’s maritime infrastructure to alleviate US maintenance and shipbuilding shortfalls.56 Bilateral maritime logistics exercises have been titled Interchangeable Logistics Exercises, highlighting the depth and familiarisation of the logistics-sharing relationship.57

By comparison, the logistics sharing potential within the US-Australia alliance is exercised with less frequency. Part of this can be attributed to US force concentration in Japan as well as the fact that there is less overlap in the usual operating areas of the USN and RAN. However, there are certain capabilities or areas where cooperation is surprisingly nascent. For instance, Talisman Sabre 2023 marked the first instance of US forces establishing a Joint Logistics Over the Shore (JLOTS) base in Australia, which facilitates expeditionary movement of equipment from ships to the beach.58 The United States and Australia, despite both operating the MH-60 helicopter, cannot embark and support one another’s aircraft due to logistical challenges.59 However, as Australia extends its gaze further from its shores and the United States is forced to examine long-held assumptions about access and resupply inside the first island chain, the two navies will more commonly sail through and rely upon the same water space, which creates more opportunities for events like the US-Japan Interchangeable Logistics Exercises.

The underlying access and sharing agreements already exist to enable this kind of cooperation, which does take place in exercises and planned engagements already, within the bilateral Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement (ACSA) which was updated in 2016.60 Nevertheless, expanding cooperation to include more operational interactions as well as the flexibility for short-notice availability would add considerable value.

Recommendations

- The USN and RAN should maintain and exercise the ability to share fuel and food stores and formally commit to doing so at the operational level of command, with a defined periodicity and short notice to participants.

- Exchange liaisons in support of combined logistics. This could take the form of liaison officers ashore, or even exchange officers working as staff augmentees within the respective logistics departments of operational staffs. Australia and the United States are already well-versed in exchanging officers at the senior staff level, with senior ADF personnel occupying key roles in the chain of command in US headquarters such as the US Pacific Fleet, and could build upon that at the working level in logistics departments.61

- Integrate combined logistics forces. This concept could also be operationalised by conducting crew exchanges between logistics ships, offering opportunities for sharing of best practices. Embarkation of allied helicopters and flight crews would be another mechanism for integration, and one that would complicate targeting of logistics vessels in a combat contingency.62

- Create a linkage between the US MSP and Australia’s Strategic Maritime Fleet to share best practices and lessons learned as Australia’s Strategic Fleet Taskforce develops the concepts and policies that will govern Australia’s capability.

Prepositioning

A central aspect of US military force projection capability is its prepositioning program, centred on a fleet of 17 ships supporting the US joint force with equipment, fuel, and other supplies.63 Separated into two squadrons, based in Diego Garcia and Guam, these ships create the framework upon which thousands of personnel can fall in upon and be fully equipped and ready for operations. However, the ships in the Maritime Prepositioning Squadrons are ageing, and increasingly the subject of cost-saving discussions that would see them either deactivated or left in a state of degraded readiness.64 Given the age and vulnerability of these vessels to a myriad of threats, particularly those posed by advanced anti-ship cruise and ballistic missiles, the future viability of these legacy platforms is certainly in question. However, the strategic logic of keeping the equipment and supplies required for combat forces deployed forward in strategic locations remains viable. As the previous section laid out, US sealift capacity is dwindling and increasingly brittle. For a force that would expect to move around 90 per cent of its equipment by sea in the event of a major conflict, present trends are distinctly unfavourable.65 In 2020, the Administrator of the US Maritime Administration (MARAD) testified that the civilian mariner workforce needed to operate the US sealift force was 1,800 personnel short of its minimum wartime requirements.66 These issues are recognised at the upper echelons of US military command, with the head of US Transportation Command, General Steve Lyons, naming sealift as the command’s “number one priority” in 2019.67 In 2020 written testimony delivered to the Senate Armed Services Committee, General Lyons cited a 59 per cent readiness level across the US sealift fleet, compared to a target of 85 per cent. At that time, Lyons indicated that over half of the US sealift fleet would be unusable by the mid-2030s.68 Efforts to reverse these trends, including divesting the fleet of obsolete ships and acquiring used ships to fill capacity gaps, are making limited progress but have yet to completely resolve the issue.69 Thus, for the coming decade, US forces are likely to require as much equipment as possible situated as near as possible to potential areas of contingency, because the sealift to move required supplies will simply not be available barring change at a speed and scale that are unlikely.

The Combined Logistics Sustainment and Maintenance Enterprise (CoLSME) offers a framework that helps solve this problem caused by ageing US sealift assets. Introduced as an initiative in the 2021 AUSMIN readout, CoLSME exists in part to “overcome logistical challenges and explore logistical opportunities in the region” with an eye toward enhancing combined warfighting capabilities, addressing both Australian and US requirements.70 Prepositioning of US Army materiel is already reportedly being planned for the support of training and exercises, with a proof of concept planned for locating US Army stores and materiel in Bandiana, Victoria following the conclusion of Exercise Talisman Sabre 2023.71 Additionally, the 2023 AUSMIN Joint Statement announced the signing of a memorandum of understanding (MOU) between the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) to jointly stage humanitarian supplies in both Brisbane and Papua New Guinea.72 The inclusion of prepositioned naval and air warfighting stocks is the next logical step for the alliance. Ensuring this materiel is positioned forward where it can be accessed is part of underwriting a US maritime presence, as ground forces will also be required to take and hold key maritime infrastructure and geography, as well as build, clear, and defend against attack.

Australian involvement in producing key munitions and maintaining pre-staged stockpiles on Australian territory would be of enormous benefit to ensuring the viability of Washington’s forward maritime presence in the event of conflict in Asia.

The 2023 AUSMIN readout highlights another area of critical importance — munitions. As highlighted by the war in Ukraine since 2022, the expenditure rate of precision munitions in modern warfare is high, and naval warfare will certainly prove no exception to that rule. Current US posture in the Indo-Pacific limits offers US maritime forces only one place to reload within the Second Island Chain — Japan. Should Japanese facilities become unavailable, US ships and submarines would be forced to withdraw to Guam or even Hawaii to reload, wasting weeks in transit. Australian involvement in producing key munitions and maintaining pre-staged stockpiles on Australian territory would be of enormous benefit to ensuring the viability of Washington’s forward maritime presence in the event of conflict in Asia. The AUSMIN commitment to “progress the maintenance, repair, overhaul, and upgrade of priority munitions in Australia, with an initial focus on Mk-48 heavyweight torpedoes and SM-2 missiles” is a positive step in this direction.73 With particular regard to the Mk-48 Mod 7 Common Broadband Advanced Sonar System (CBASS), which was a co-development project between the United States and Australia, creating the ability for Australia to maintain weapons without support from US industry or US-based facilities is a critical alliance capability.74 For strike weapons that were not co-developed, such as the RIM-66 (SM-2), RIM-174 (SM-6) and Tomahawk, the path toward co-production and maintenance is more complex. Australia’s Guided Weapons and Explosive Ordinance (GWEO) enterprise, which exists to bring Australia more directly into the manufacturing of priority munitions, is moving slower than desired due to bureaucratic slowness on the US side in overcoming export control hurdles.75

Recommendations

- Offer pier space in Australia for US MPSRON ships. Existing pier space is in demand, which means this recommendation could require the addition of a new pier at an existing port, likely in Western Australia. One option could include a dedicated pier within the Gascoyne Gateway port facility, should the commercial operators agree to such an addition. Its deep water location and relatively uncrowded surroundings could be a suitable fit for prepositioning ships, which on average draw approximately 10 metres under the keep and measure around 200 metres or more in length.76 Creating optionality to shift away from known basing locations in Diego Garcia and Guam complicates targeting of a critical capability. Diversifying operating areas also brings with it more options for employing these ships and bringing them forward for operations such as humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR). While Australia’s port infrastructure and empty pier space are not infinite, plans to further develop Western Australia’s Henderson port facility could offer the opportunity for expansion to host these critical ships.

- Within CoLSME, explore transitioning afloat prepositioned stocks from MPSRON ships that may be unfit for service or decommissioned into ashore facilities in or around Darwin and Fremantle. The fact that the Darwin Port lease is held by a Chinese-owned company, and likely will be until 2114, does pose serious security questions that would need to be answered before pursuing that option, ranging from security of networks to physical security of equipment.77 While stationary materiel concentrations are still targetable by long-range ballistic missiles, it complicates targeting of key war stocks and creates an element of resilience. This could also include forward basing of smaller sealift platforms and maritime logistics capabilities, such as the Expeditionary Fast Transport (EPF), which could move smaller amounts of materiel into key geographies without the scale and radar cross-section of traditional prepositioning vessels.

- Ensure initial execution and sustained investment in the production, maintenance, and stockpiling of key naval munitions in Australia for use by both alliance partners. Developing the ability to produce and maintain weapons including the Mk-48 torpedo and SM-6 and Tomahawk missiles will require significant export control and tech transfer reform on the US side, but would be an important addition to efforts intended to reinforce US maritime deterrence in the region.

Maintenance

US policymakers are struggling to arrest a long declining trajectory in US domestic maritime infrastructure, with alarmingly outdated facilities and a shrinking workforce causing problems across the spectrum of shipbuilding to maintenance. In 2022, the US Navy’s four public shipyards had 1,200 fewer workers than they required, with intense competition for skilled labour and the knock-on effects of COVID-19 limiting government success in recruiting the workforce required.78 Private shipyards are also critically understaffed in key shipbuilding trades and preparing for a “silver tsunami” which will see hundreds of master shipbuilders and thousands of skilled workers on the verge of retirement, without sufficient numbers of workers being trained to replace them.79 In an effort to address this decline, the US Navy initiated the Shipyard Infrastructure Optimization Program (SIOP) in 2018, a US$21 billion effort to modernise the country’s four public shipyards.80 While the SIOP has made observable progress such as breaking ground on a US$300 million effort to upgrade, repair and modernise Norfolk Naval Shipyard, these upgrades are still in early stages and the program’s shortfalls are far beyond acceptable limits.81 Estimated costs for improvement and modernisation are ballooning by billions of dollars, as are the expected timelines for completion.82 Part of the SIOP called for seismic risk evaluations of existing infrastructure, which led to the closure of four US Navy drydocks in the Puget Sound in January 2023 because of an identified risk of catastrophic damage to the facilities in a potential seismic event.83 The country’s four public shipyards operate a total of 18 drydocks, meaning this closure represented a loss of 22 per cent of US drydock capacity.84 This significant reduction in capacity is also a reminder of the lack of modern investment in new US maritime facilities — the four closed drydocks are some of the country’s newest, and three of them were built before the Vietnam War. While a drydock’s age is not necessarily a limiting factor — Captain Cook Graving Dock opened on Sydney’s Garden Island in 1945 — the US Navy’s Report to Congress on the Long-Range Plan for Maintenance and Modernization of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2020 stated: “In 2018, most naval shipyard capital equipment was assessed as beyond effective service life, obsolete, unsupported by original equipment manufacturers, and at operational risk. This aged equipment increases submarine and aircraft carrier depot maintenance costs, schedules and reduced [shipyard] capacity.”85

Without considerable increases in capacity, the US Navy will be unprepared to repair and revive ships and submarines that would inevitably be damaged in a high-end contingency against a peer competitor. A 2020 US Government Accountability Office (GAO) study found that between fiscal years 2015 to 2019, 75 per cent of planned maintenance periods for both submarines and aircraft carriers were completed late, one of the leading reasons for which was shipyard workforce performance and capacity.86 In total, those delays accounted for 7,424 days of delays. In late 2022, 18 of the US Navy’s 50 attack submarines were either in maintenance or awaiting yard availability to begin maintenance. The closure of Dry Dock 6 at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard & Intermediate Maintenance Facility is particularly significant, as it is the only west coast facility capable of accommodating a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier.87 Until it is reopened, any US CVN (Carrier, Volplane, Nuclear) needing drydock-level maintenance will have to transit to the east coast of the United States to the last remaining facility capable of accommodating them. In 2023, GAO released another report indicating that maintenance delays, along with several other critical issues, were resulting in ballooning costs as well as a decrease in steaming hours — hours the ships were at sea conducting either training or operations. Across 10 classes of US ships, those increasingly scarce steaming hours also became more expensive.88 This shortfall of maintenance and repair capacity results in deferred maintenance, meaning that the US Navy is unable to service its equipment on the established schedule laid out for its platforms and begins to incur risk, the severity of which is often underestimated. Deferring maintenance means that ships and submarines break down more often and are in worse shape when they are eventually admitted for maintenance, resulting in longer maintenance periods which then contribute to the vicious cycle of maintenance delays. For instance, the US Navy’s submarine force operates under the assumption that approximately 10 per cent of its boats will be undergoing maintenance at any given time. In the 2022 fiscal year, maintenance delays resulted in a further reduction in strength by eight boats that were either waiting for maintenance or took longer than expected to repair.89 Adding ready capacity abroad, rather than trying to grow or build it at home, is an easier road to reaching the required targets and this is an area where Australia’s own maritime industry could play a significant role.

Without considerable increases in capacity, the US Navy will be unprepared to repair and revive ships and submarines that would inevitably be damaged in a high-end contingency against a peer competitor.

US legal statute restricts types of maintenance that are allowed to be performed by overseas shipyards. Given shortfalls in US maintenance capability, this is an area where radical change should be considered. US Code already allows for some degree of overseas maintenance, particularly with regard to mid-voyage repairs, but not in the level of detail required to meet new operational realities. Encouragingly, expanding these options in Australia was a priority item identified during the 2021 AUSMIN, specifically identified in the accompanying joint statement.90 A US delegation visited bases and other facilities in 2022 to this end as well.91 Both were actually predated by an Agreement of Boat Repair (ABR) between Austal and the US Navy which was put into place in 2020, opening the door to Australia’s Austal to bid for and provide emergent support services to US vessels in Australia.92 Repairs, maintenance and sustainment were all included in the agreement’s scope, with Austal completing its first successful contract in 2022 with a mid-voyage repair of USS Ashland (LSD-48).93 In a similar vein, since a 2022 agreement from the US-India 2+2 Ministerial Dialogue for the United States to use repair facilities in India, Military Sealift Command has sent two of its Lewis and Clark-class dry cargo ships to a shipyard in Kattupalli for scheduled voyage repair availability (VRAV) maintenance periods.94

Australia’s own maritime infrastructure is a critical industry that requires a steady pipeline of work to keep facilities operating and high-skilled workforces gainfully employed. Sydney’s Captain Cook Graving Dock (CCGD), located on Garden Island, remains one of the Southern hemisphere’s largest ship maintenance and repair facilities.95 Measuring 350 metres by 45 and holding 230 million litres of water, the CCGD can accommodate both navies’ amphibious assault ships (LHDs). It is also the only facility of its kind in Australia capable of accommodating ships over 12,000 tonnes.96

The Henderson drydock announced by the Morrison government would be an important addition to Australia’s maintenance capacity, particularly in Western Australia where the submarines of SRF-West will be based. However, this facility, originally intended to begin operations in 2028, has yet to materialise beyond the initial announcement, with no funds ever allocated for its construction.97 Such a facility will be required to support the submarines of SRF-West as well as the RAN’s planned AUKUS-class boats into the future, and could also alleviate critical shortfalls in US capacity. Austal USA’s 2022 contract win for an Auxiliary Floating Dry Dock Medium to be supplied to the US Navy is also an interesting development which might open the door to more bilateral cooperation in the space. While the current government in Canberra makes determinations regarding the Henderson dry dock, and Austal USA moves forward with their entry into the floating drydock market, the timing might be right for the alliance to partner on drydock technology. Submarine-ready drydocks will be a vital necessity for SRF-West to become a meaningful operational capability, and the ability of Australian industry to contribute to that capability will be valuable. While it is not as advanced as other technologies currently being evaluated within AUKUS’s Pillar II, partnering on drydock technology offers a less-sensitive on-ramp toward increased technology sharing which remains a politically difficult issue in Washington.98

Australian industry is already intimately familiar with two of the US Navy’s newest classes of ship — the Independence-class Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) and Spearhead-class Expeditionary Fast Transport (EPF) — which are built by its American subsidiary, Austal USA.99 Austal’s American arm is also building its first steel-hulled ships for the US Navy, the Navajo-class Towing, Salvage and Rescue Ship (T-ATS).100 This fact alone makes Austal a natural maintenance and repair partner for US Navy ships that will be increasingly present in the Indo-Pacific. As US shipyards struggle to meet maintenance demand, Australian facilities should increasingly be seen as a viable backup to US domestic capacity. Australia’s planned network of Regional Maintenance Centres (RMCs), beginning with the completed RMC in Cairns and targeting a 2024 completion date for RMC East in Sydney, with additional locations proposed for Darwin (North), and Henderson (West) will create significant opportunities to realise this aspirational capability.101 The RMCs are intended to coordinate and deliver maintenance through a standardised system using a unified national approach, which integrates industry and defence and should simplify planning for visiting ships seeking maintenance.102 While this network will first begin to realise additional capacity for maintaining surface vessels, it will likely offer a similarly improved level of maintenance capability for submarines as it matures.103

The commonality of platforms is also increasingly normal between the two navies, and this interchangeability creates significant opportunities for maintenance interactions, particularly in Australia. The RAN’s Hobart-class Air Warfare Destroyers operate the SPY-1D(V) radar system and Aegis combat system and contain a considerable amount of other US-origin technology including the Mk-41 Vertical Launching System (VLS), AN/SPQ-9B Horizon Search Radar, Phalanx Close-in Weapons System and others which are maintained by a combination of Australian shipyard workers and tech support personnel travelling to Australia from the United States.104 The maintenance of the RAN’s Air Warfare Destroyers’ weapons systems and combat system is managed through a Foreign Military Sales (FMS) case through the US Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA), which is also how the ships’ AEGIS spiral upgrade program is administered. However, with only three ships in the class, there are bound to be gaps in maintenance schedules when trained personnel are not actively engaged. Those gaps could and should be filled by US Navy ships. Australian shipyards are also already capable of conducting the types of routine diesel engine and Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) maintenance that US ships require.105

Beyond surface vessels, a similar approach should also be taken to naval aviation capabilities. Referencing the aforementioned challenges to integrating the MH-60R Seahawks afloat, Sikorsky Australia carried out a successful proof of concept for executing deep maintenance of a US asset in Australian facilities. A US Navy aircraft arrived in Sikorsky Australia’s Nowra, NSW facilities in October to execute a planned maintenance interval (PMI), which was successfully concluded in June 2023.106 Sikorsky Australia has already performed over 40 PMIs for Australian aircraft, obviating the requirement to send those aircraft back to a US depot, where that type of maintenance would normally be performed.107 Similarly, Boeing Defence Australia inaugurated its capability to conduct deep maintenance on Australia’s P-8A fleet at RAAF Base Edinburgh in South Australia in 2022.108 This is a capability that could conceivably enable US P-8As, commonly deployed to Okinawa and elsewhere in the Indo-Pacific, to receive similar maintenance in Australia when required, rather than being sent back to US facilities. Taking advantage of these pre-existing and rapidly developing capabilities in Australia would not only raise the readiness levels of US forces but keep them present in the region as well as provide steady levels of profit generation for the Australian maritime industry.

The issues and resolutions presented here are admittedly complicated by the fact that Australia is not the only US ally with excess maintenance capacity and interchangeable technology. Japan, for instance, has also begun to publicly indicate its interest in bringing more US ships to Japanese ports for this kind of maintenance.109 The emphasis on the US maintenance partnership with India will also continue. However, US maintenance shortfalls seem to indicate that there is enough work to go around. Washington’s desire for contingency access will rely on creating the necessary relationships and workforce stimulus in peacetime, such that finding ways to keep work flowing into multiple partners’ repair facilities will simply be a requirement, albeit one that may need to be approached creatively and flexibly.

Recommendations

- Advance planning for Western Australia drydock. Increased engagement from the Australian Government in delivering a firm plan for an on-shore drydock serving HMAS Stirling and SRF-West would be an incentive for commercial investment. It would also underwrite the Australian Government’s commitment to the 2023 Defence Strategic Review and the operational side of AUKUS, by committing funds and political attention to the types of large-scale infrastructure projects that will be required to support a domestic nuclear-powered submarine program as well as the preceding trilateral combined submarine force.

- Build a combined maintenance plan for combatants and auxiliaries. This would be best approached in a phased plan, including first those ships built by Austal USA, then growing to include more US combatants as the program is successful. This will require significant political effort on the US side, to amend or repeal existing US federal statutes restricting conducting significant maintenance in non-US ports for ships based in the continental United States. Chief among these is US Code Title 10 § 8680, which governs restrictions on overhaul and repair of vessels in foreign shipyards.110

- Facilitate transfer of US floating drydock technology. This might best be approached through an avenue such as AUSMIN. While floating dry dock is a proven technology, associating this key item with AUKUS Pillar I/II in some respect might provide bureaucratic strength to the case for expediting transfer and ensuring rapid development and deployment. This is a significant capability that would be beneficial to a trilateral submarine force, particularly when considering potential future contingencies that could involve damage to boats but would also be critical for ensuring alliance capability to refuel, rearm, resupply, repair and revive surface forces.